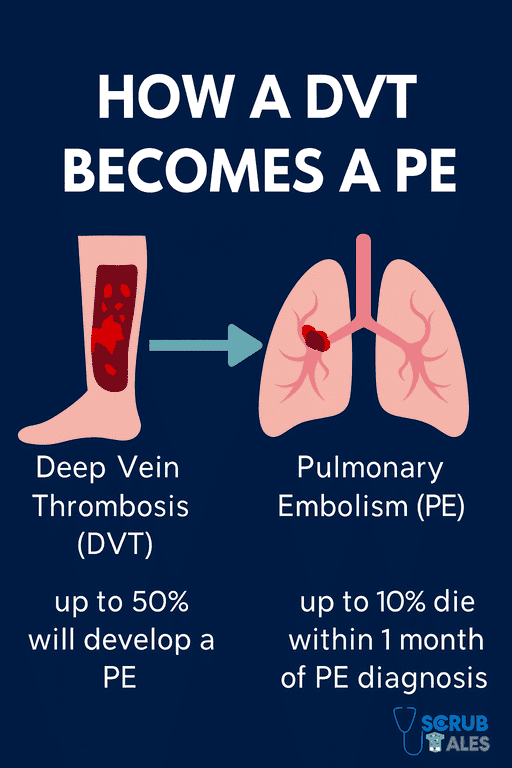

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) refers to blood clots forming in the venous circulation. It includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, both of which are serious and potentially fatal.

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is the collective name for methods used to prevent these clots in high-risk patients. It is a cornerstone of inpatient care and hospital safety.

Patients admitted with trauma, undergoing surgery, or with prolonged immobility are especially at risk. Without preventive strategies, the risk of venous thromboembolism increases, making them vulnerable to clots forming in the legs (DVT) or lungs (PE).

Medical practitioners — including doctors, pharmacists, and nurses — must apply current venous thromboembolism prophylaxis guidelines to prevent avoidable harm.

If you’re applying for NHS jobs, ensure your TRAC supporting statements reflect your awareness of safe prescribing practices, such as VTE prevention.

Why VTE Prophylaxis Matters

Hospital patients are often immobile, post-op, or acutely unwell — prime conditions for clot formation.

Without prophylaxis, VTE affects thousands every year. With it, we save lives.

Healthcare professionals and organisations should implement VTE prophylaxis guidelines to reduce preventable harm. Implementation is one of the crucial yet commonly overlooked steps during the clerking of a patient while on call.

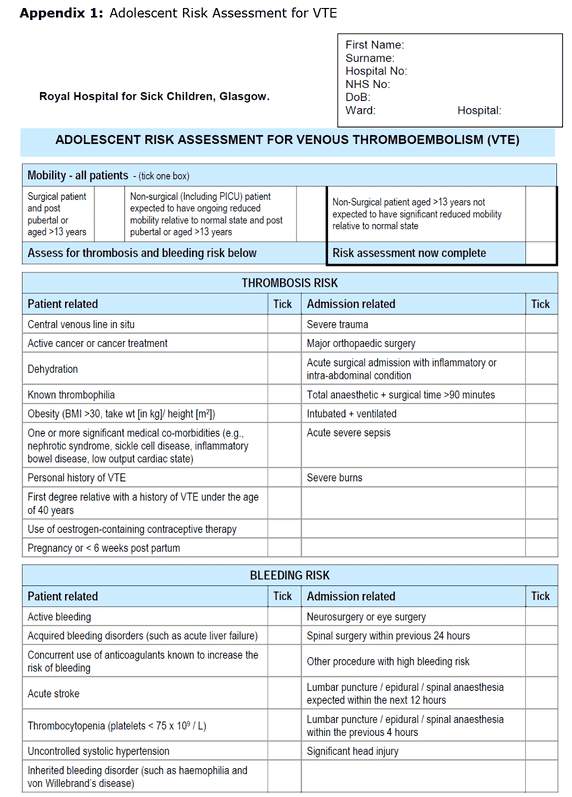

Risk Factors and VTE Assessment

Every patient admitted should be assessed for venous thromboembolism within 24 hours. The patient’s condition, risk factors for VTE, and bleeding risk must all be considered when planning prophylaxis.

Specific indicators are used to guide risk assessment and inform decisions regarding prophylaxis.

This involves assessing both:

- Clot risk (e.g. immobility, surgery, cancer)

- Bleeding risk (e.g. active bleeding, low platelets)

A record of VTE assessments must be documented in the thromboprophylaxis section of patient records.

Certain patient factors and conditions increase the risk of VTE.

Risk Factors for Thrombosis

- Immobility (e.g. prolonged bed rest or paralysis)

- Major surgery (primarily orthopaedic or pelvic surgery)

- Trauma (significant injuries or fractures)

- Active cancer or recent cancer treatment

- History of VTE (previous DVT or PE)

- Hormone replacement therapy or oral contraceptive use

- Pregnancy and the postpartum period

- Obesity and increasing age

- Varicose veins (especially with phlebitis or leg swelling)

Bleeding Risks That May Contraindicate

- Active or recent bleeding

- Thrombocytopenia

- Stroke in the past 4 weeks

- Spinal/epidural catheter in situ

Use the NHS VTE risk assessment tool, available in most hospital e-prescribing systems or clerking packs. If unsure, always follow NICE guidelines.

Patient's risk of bleeding and VTE should be reassessed within 48-72 hours of admission.

Tools to Support Risk Stratification

Some trusts use formal scoring systems like:

- Padua Score (for medical patients)

- Caprini Score (for surgical patients)

- IMPROVE model (ICU patients)

These tools provide essential information to guide clinical decisions regarding VTE prophylaxis and establishing a VTE risk assessment score.

But even without scoring, the principle remains:

→ Identify risk factors

→ Balance with bleeding risks

→ Decide on prophylaxis

Risk should be reassessed throughout the admission as the patient's condition evolves.

Pharmacological Interventions

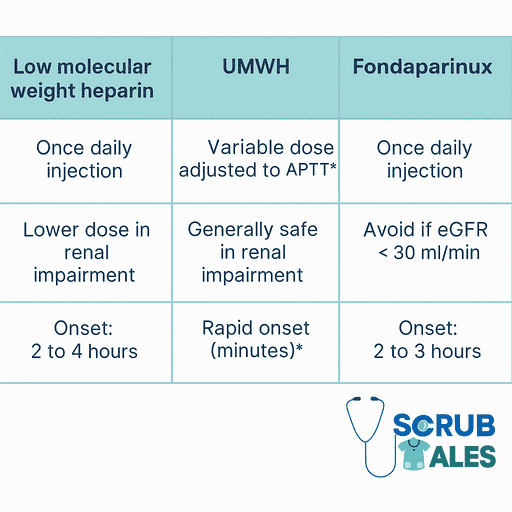

First-line: LMWH

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the standard.

Usually:

- Enoxaparin 40 mg SC once daily

- Dalteparin or Tinzaparin in some trusts

Dose adjustments are needed if:

- Weight >150 kg or < 40 kg

- Renal impairment (e.g. CrCl < 30)

In such cases, reduce the dose or consider unfractionated heparin (UFH). Trust-specific guidelines for enoxaparin (Clexane) are recommended.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is a potential complication in some patients and must be actively monitored, mainly when low molecular weight heparin is used. Prompt diagnosis of HIT is crucial for patient safety and to ensure appropriate management.

Recommendations include careful consideration of contraindications when prescribing enoxaparin.

Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices may be preferred for patients with high thrombotic risk when LMWH is contraindicated.

Alternatives to LMWH

- Fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily – useful if HIT risk or allergy

- UFH 5000 U SC TDS – in renal failure or high bleeding risk

- DOACs – used in orthopaedic post-op settings (e.g. rivaroxaban)

Aspirin is not used outside of orthopaedics. It's not potent enough for general medical VTE prevention.

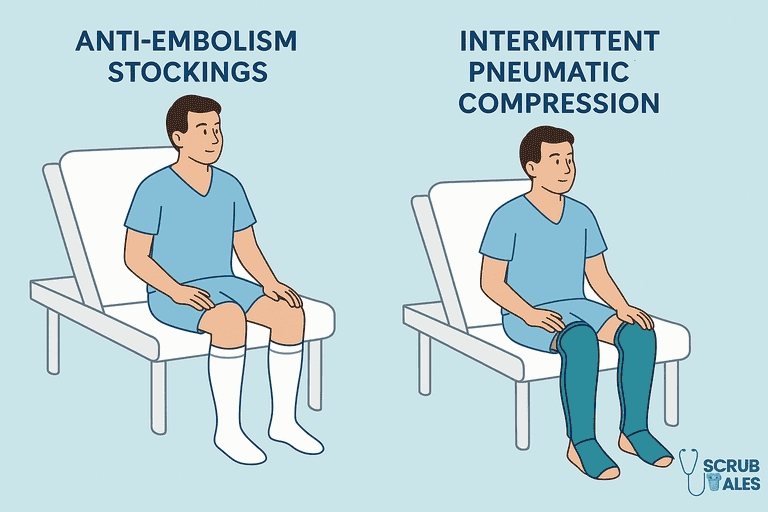

Mechanical VTE Prophylaxis

Used when meds are contraindicated or as an add-on. Mechanical thromboprophylaxis includes the use of anti-embolism stockings (AES) and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices.

Patients with significant renal impairment may have an increased bleeding risk when using LMWH, which suggests mechanical options may be preferred.

Options:

- Anti-embolism stockings (AES): Apply pressure at the ankle and calf. Continual observation and assessment are required to ensure proper fit and patient safety.

- Intermittent Pneumatic Compression (IPC): Leg sleeves or foot pumps

- Early mobilisation and hydration – don’t underestimate these!

Anti-embolism stockings are commonly utilised as a form of mechanical thromboprophylaxis to prevent VTE.

Incorrect fitting of anti-embolism stockings can cause skin damage, requiring careful monitoring and assessment by healthcare providers.

Caution: Avoid stockings if the patient has:

- Peripheral arterial disease

- Massive oedema

- Open leg wounds

- Fragile skin

Patient-Specific Prophylaxis

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

The main users of VTE prophylaxis include surgical patients, trauma patients, and those with cancer or hormone-related risk factors.

A tailored strategy should consider the patient’s procedure, medical history, stroke or trauma status, and cancer or hormone-related risk factors.

Mechanical methods, such as intermittent pneumatic compression devices, are used when bleeding risk is high or as adjuncts.

Legs should be monitored for signs of deep vein thrombosis, such as redness, swelling, or tenderness.

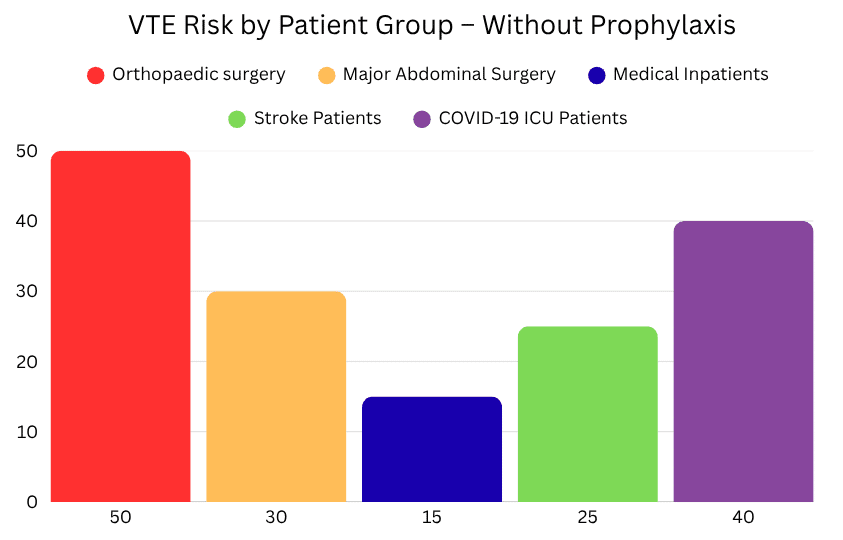

VTE Prophylaxis in Medical Patients

Medical patients account for a significant number of hospital-acquired VTEs.

Common high-risk cases:

- Pneumonia

- COPD exacerbation

- Heart failure

- Stroke

- COVID-19

Start LMWH if the patient is immobile and has no bleeding risk.

Continue for at least 7 days, even if discharged early.

Stroke Patients

- The CLOTS3 trial recommended IPC for use in patients immobilised after an acute stroke, highlighting its safety.

- Use IPC sleeves within 3 days

- Do not use stockings in immobile stroke patients

- Consider starting LMWH after the acute phase, especially if no bleeding

For patients with confusion or cognitive impairment, it’s also essential to check the confusion screen bloods before planning LMWH self-injection.

ACS and COVID Patients

- ACS on full antiplatelets may not need LMWH

- COVID-19 patients have high clot risk → give LMWH unless contraindicated

- Intermediate dosing is sometimes used in the ICU (trust-dependent)

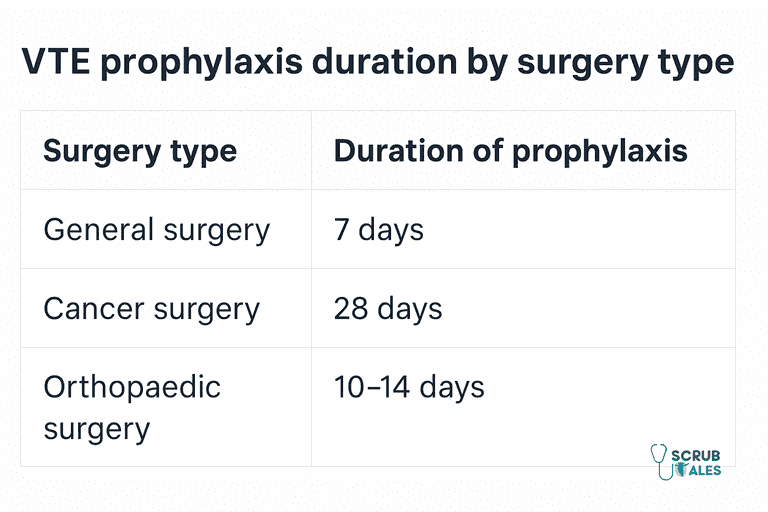

VTE Prophylaxis in Surgical Patients

Surgical patients often have multiple clotting risk factors:

- Immobility

- Tissue trauma

- Inflammation

- Post-op recovery time

That makes VTE prevention vital, especially in abdominal, cancer, and orthopaedic surgeries.

Enoxaparin should be administered in a timing-specific manner based on the type of patient and their surgical schedule.

Patients admitted on the same day of surgery should also be assessed for VTE and may require AES and LMWH if indicated.

General Surgery

- Start LMWH 6–12 hours post-op (once bleeding risk is low)

- Use mechanical methods (IPC, stockings) intra- and post-operatively

- Mobilise patients early

For abdominal/pelvic cancer surgeries, consider 28 days of LMWH post-op.

This extended course significantly lowers post-discharge PE risk.

Elective Hip and Knee Replacements

These are high-risk procedures. NICE recommends specific regimens:

Hip Replacement

- LMWH for 10 days, then aspirin for 28 days

- OR rivaroxaban for 35 days

- OR LMWH alone for 28 days

Knee Replacement

- Aspirin alone for 14 days

- OR LMWH or DOACs for 14 days

Start LMWH 6–12 hours after surgery. Add stockings if the patient is immobile.

Hip Fracture Surgery

In elderly or trauma patients:

- Use LMWH for 28–35 days post-op

- If surgery is delayed, consider pre-op LMWH unless the bleeding risk is high

- IPC devices help if LMWH is contraindicated

Always review mobility status daily.

Minor Ortho and Limb Immobilisation

- Short knee scopes <90 mins → no prophylaxis needed

- Immobilised lower limb (e.g. cast) → consider LMWH if >42 days

Upper limb surgery rarely requires VTE prophylaxis unless it is high-risk.

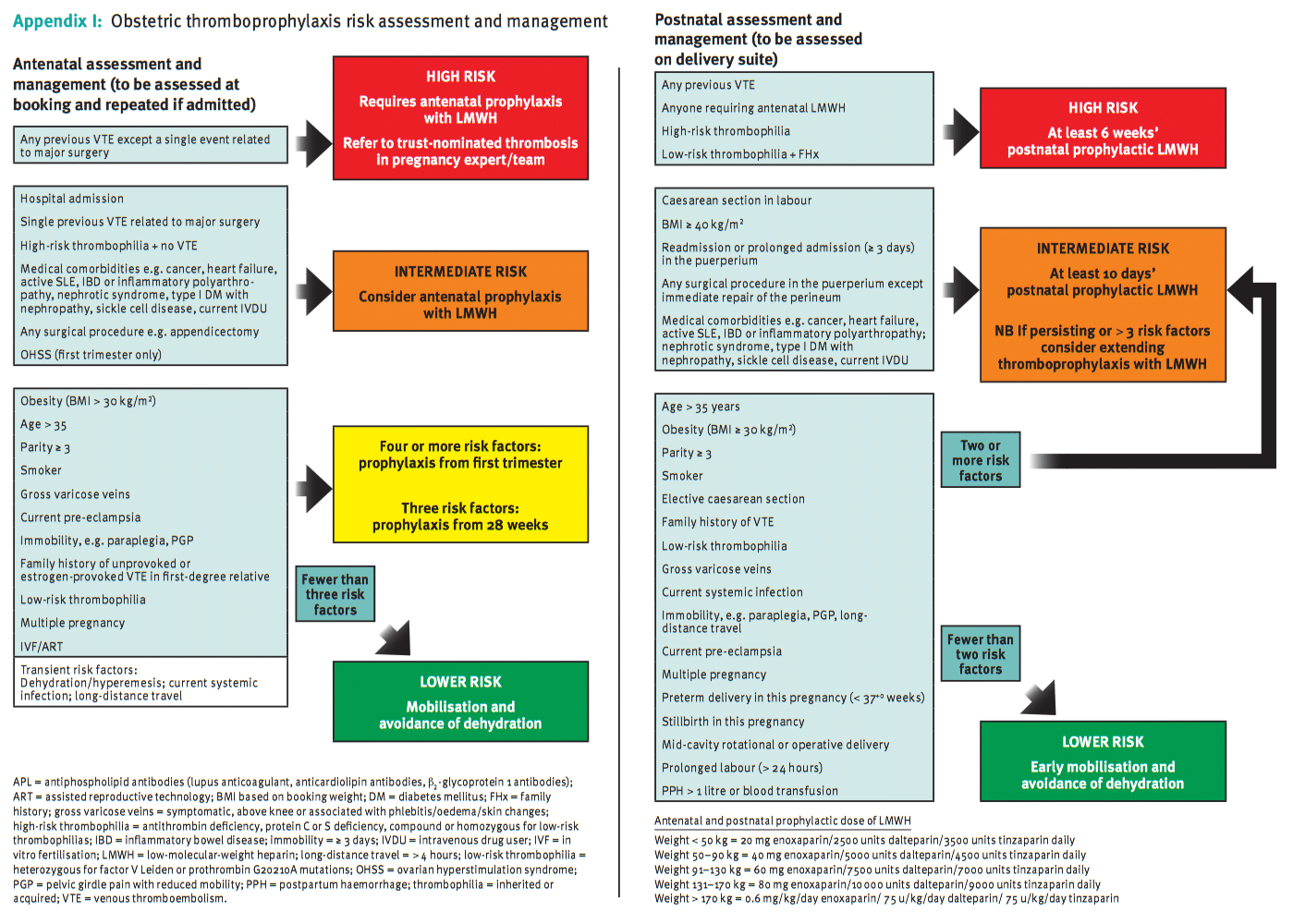

VTE Prophylaxis in Pregnancy and Postpartum

Pregnancy is a naturally hypercoagulable state. VTE is a leading cause of maternal death in the UK.

There is a well-explained chart on the NICE guidelines for VTE on the official pregnancy website.

Risk is highest:

- In the third trimester

- During labour/delivery

- And especially in the first 6 weeks postpartum

VTE Risk Assessment Pregnancy

- Done at booking and updated if risk changes

- Reassess after delivery

- Points assigned for BMI, C-section, age, immobility, multiple pregnancy, etc.

Who Gets Prophylaxis?

- Prior VTE or thrombophilia → Antenatal + Postnatal LMWH

- Emergency C-section + ≥1 risk factor → 10 days postnatal LMWH

- High risk postpartum → 6 weeks LMWH

What to Use

- LMWH is first-line (e.g. enoxaparin)

- Dosed by booking weight

- Safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Avoid warfarin and DOACs (cross placenta / teratogenic)

- Aspirin is not effective for VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy

Around Delivery

- Withhold LMWH 24h before planned induction or spinal/epidural

- Restart 6–12h postpartum once bleeding risk is acceptable

- Use mechanical methods (IPC, AES) around the time of delivery

Special Considerations

Renal Failure

- Use UFH instead of LMWH if CrCl <30

- UFH is not renally cleared

- In patients with renal impairment, the risk associated with anticoagulants must be carefully evaluated before prescribing.

Obesity

- May need higher dose LMWH

- Check local protocol or use anti-Xa monitoring

Bleeding Risk

- Use mechanical methods only until bleeding resolves

- Reassess daily

HIT History

- Avoid all heparins

- Use fondaparinux or danaparoid

Already on Anticoagulation

- Don’t double up

- If anticoagulant is paused, consider LMWH cover during the gap

Summary Table: VTE Prophylaxis by Scenario

| Scenario | Recommended Prophylaxis |

|---|---|

| Medical inpatient | LMWH 40 mg daily for 7 days or until mobile |

| General surgery | LMWH post-op; 28 days if cancer surgery |

| Hip replacement | LMWH 10 days + aspirin 28 days OR DOAC 35 days |

| Knee replacement | Aspirin or LMWH/DOAC for 14 days |

| Hip fracture | LMWH for 28–35 days |

| Pregnancy – high risk | LMWH antenatal + 6 weeks postnatal |

| Postnatal – moderate risk | LMWH for 10 days |

| Stroke (immobile) | IPC within 3 days |

| Bleeding risk | Mechanical only |

| CrCl <30 | UFH instead of LMWH |

General Recommendations and Guidelines

VTE prophylaxis decisions should be rooted in evidence-based practice.

Guidelines such as those by NICE are regularly reviewed and updated in light of new evidence or clinical trial results, ensuring that current evidence supports every recommendation.

Healthcare professionals must:

- Stay updated on the latest VTE prophylaxis NICE guidelines

- Apply guideline-driven risk assessments

- Reflect on and adjust decisions as clinical situations change

- Choose the way to implement recommendations that aligns with local priorities and ethical responsibilities

Patients should be informed about the rationale behind VTE prophylaxis, particularly when compression stockings or injections are involved. Awareness improves compliance and early reporting of complications.

Pharmacists and the wider multidisciplinary team (MDT) play a crucial role in reviewing drug charts and ensuring timely VTE prophylaxis.

Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in Special Populations

Some groups require adapted strategies:

- Cancer patients are highly prothrombotic and often need extended prophylaxis.

- Stroke patients, particularly those with limb weakness, need early mechanical prevention and cautious pharmacological decisions. Patients admitted for stroke rehabilitation often use IPCs for VTE prophylaxis, especially if they are immobile.

- Pregnant women, especially post-cesarean or with varicose veins, should be offered LMWH over warfarin or DOACs. The risk of VTE is significantly increased in pregnant women and those who have recently given birth.

- Patients with a history of DVT or PE must be monitored closely, even if they appear stable.

- Those on hormone replacement therapy or oestrogen-based contraception have an added risk and need more vigilant assessment.

(Further details on prophylaxis in specific populations can be found in specialised resources. Always refer to the latest guidelines for nuanced recommendations in these scenarios.)

Anti-embolism stockings are the most commonly used form of mechanical thromboprophylaxis for preventing VTE.

In frail or palliative patients, you may also consider ceilings of care or DNAR decisions, which should align with your VTE approach.

Renal impairment is associated with an increased anticoagulant-related bleeding risk in patients when managing VTE.

Patients with severe renal impairment may require withholding enoxaparin and applying mechanical thromboprophylaxis instead.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Prophylaxis doesn’t end with prescribing. In emergencies like suspected PE, timely escalation following Advanced Life Support (ALS) principles is vital.

All patients should be monitored for:

- Bleeding complications

- Signs of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

- Progression of symptoms suggestive of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism

The patient’s risk and plan should be reviewed at regular intervals, especially during significant changes in health status. Any changes or complications should be clearly noted in the patient’s records.

Patient education is also vital. Before discharge, patients should be informed of signs to watch for (such as leg pain or breathlessness) and how to seek help.

Healthcare teams must ensure that the guideline is followed, not just at admission, but also through follow-up and post-discharge care.

Final Tips

- Risk assessment on admission and regularly after

- Encourage early mobilisation and hydration

- Prescribe correct dose, route, duration

- Document plan clearly in notes and discharge letters

- Teach patients (especially post-op or postpartum) to self-administer LMWH if needed

- Don’t forget—clear documentation of your prophylaxis plan is not just good practice, it’s part of your medical indemnity protection.

Want to improve VTE compliance in your ward? You can lead a clinical audit—we’ve created a free Excel tool to help you get started.

FAQs

What drug is used for VTE prophylaxis?

The most commonly used medication for VTE prophylaxis is low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), such as enoxaparin or dalteparin. These are administered via subcutaneous injection once daily and are effective in reducing the risk of clot formation.

What does VTE mean?

VTE stands for venous thromboembolism, which includes both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) — blood clots that form in the veins and can be life-threatening if not treated.

Which patients need VTE prophylaxis?

Most patients admitted to the hospital — especially those who are immobile, undergoing surgery, have active cancer, or are pregnant — should be assessed for and often receive VTE prophylaxis, unless contraindicated due to bleeding risk.

What is VTE treatment?

VTE treatment involves therapeutic anticoagulation, such as higher doses of LMWH, DOACs (like rivaroxaban), or warfarin, to dissolve or stabilise an existing clot. This is different from prophylaxis, which aims to prevent clots from forming.

Can I use aspirin instead of LMWH?

Only after hip/knee surgery. Not in medical patients or pregnancy.

What if a patient’s bleeding risk is high?

Use mechanical methods and reassess daily. Start meds when safe.

Do I continue LMWH after discharge?

Yes, if:

– Hip/knee replacement

– Major cancer surgery

– Pregnancy with risk factors

Are DOACs used for VTE prophylaxis in the hospital?

Only in selected ortho cases. Not routinely in medical patients.

Do I need to risk assess every patient?

Yes — it’s an NHS requirement. Use the trust VTE tool.

What is the most common VTE prophylaxis used in hospitals?

LMWH, typically enoxaparin once daily, is first-line for most inpatients.

Can I use DOACs for VTE prophylaxis in medical patients?

Usually reserved for surgical patients post-discharge; not routine in medical inpatients.

When should I stop VTE prophylaxis?

Once the patient is mobile and the risk is resolved, or if contraindicated (e.g. active bleeding).

Is mechanical prophylaxis enough on its own?

Yes, in patients where bleeding risk precludes pharmacological methods.

What if my patient is already on anticoagulation?

No need for prophylaxis – they’re already covered.

Are there any scoring systems?

NHS uses a standard VTE risk assessment tool; the Padua score and IMPROVE Bleeding Score are also referenced in some settings.