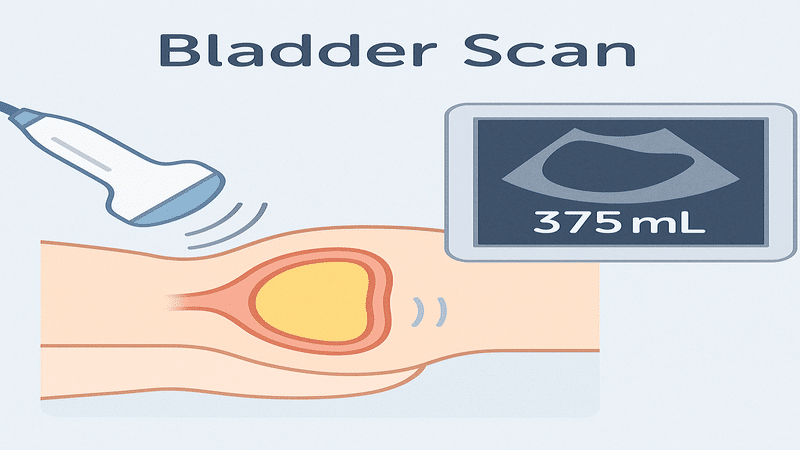

A bladder scan is a quick, non-invasive ultrasound of the bladder that measures the amount of urine it contains. In NHS practice, bladder scanning is often used at the bedside to assess urinary retention and avoid unnecessary catheters.

It gives instant, pain-free insight into bladder volume so clinicians don’t have to resort to invasive measures.

What is a Bladder Scan?

A bladder scan (sometimes called a bladder ultrasound) uses a handheld ultrasound device (a bladder scanner) to measure the volume of urine in the bladder. The scanner emits sound waves into the lower abdomen and calculates the bladder volume based on the echoes returned.

This is a non-invasive procedure that can be performed by trained nurses or doctors in seconds. It’s generally very safe – no radiation and no more discomfort than a bit of gel and gentle pressure on the abdomen.

Why use an ultrasound instead of a catheter?

Bladder scans can check for residual urine without the risks associated with inserting a catheter. National guidance recommends using a bladder scan in preference to an indwelling catheter when checking post-void residual urine, because it’s more comfortable and has fewer adverse effects.

In other words, if we only need to measure urine volume (and not necessarily drain it immediately), scanning is the first choice in modern NHS practice. This reduces unnecessary catheterisations, lowers the risk of infection and urethral trauma.

Why and When are Bladder Scans Used?

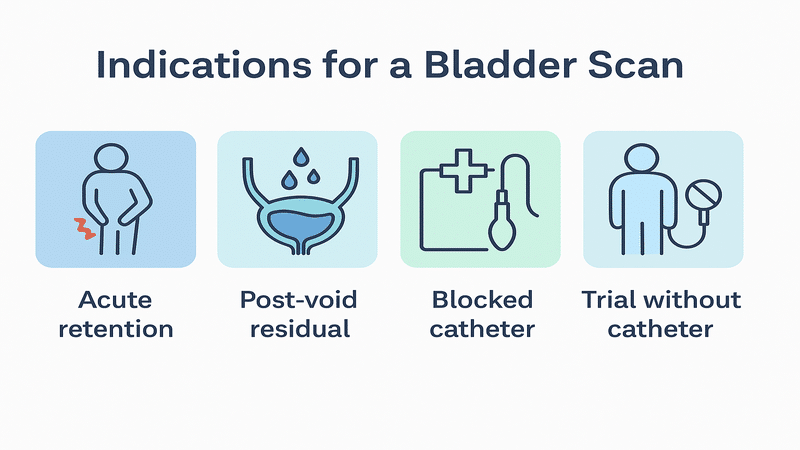

Bladder scans are used to determine the amount of urine in the bladder. Common indications include:

- Suspected urinary retention: If a patient hasn’t passed urine for several hours or exhibits symptoms of incomplete emptying, a bladder scan can confirm whether urine is being retained. For example, a patient after surgery or an older man with prostate issues might have a full bladder that they can’t empty. Scanning can quickly show if there’s, say, 600 mL still in the bladder, so acute retention needs a catheter.

- Post-void residual measurement: For patients with urinary problems (like overflow incontinence or neurogenic bladder), a scan after voiding checks how much urine remains. A high residual volume (e.g. 200+ mL) suggests incomplete emptying and possible bladder dysfunction.* Avoiding unnecessary catheterisation: Used to decide if a catheter is needed. For example, nursing staff might scan a patient who hasn’t voided to see if the bladder is full. If the scan shows only a small volume, one might not catheterise and try other measures. This is standard to prevent invasive procedures.

- Blocked catheter check: If a patient has a catheter in place but no urine is draining, a quick bladder scan can tell if the bladder is filling up. If the scanner shows a large volume despite the catheter, the catheter may be blocked – time to flush or replace it.

- After removing a catheter (Trial Without Catheter, TWOC): When a catheter is taken out, we often scan the bladder the next time the patient urinates. This checks if they emptied well or if a significant amount of urine is retained, so we can determine if the catheter needs to be reinserted.

- Monitoring chronic retention or bladder function: Patients with chronic urinary retention, spinal injuries, multiple sclerosis, or other conditions might get regular bladder scans to monitor residual volumes. It helps us adjust treatments and prevent complications like kidney damage from long-term retention.

- Postoperative or postpartum urinary care: In some protocols, if a patient hasn’t voided within a specific time after surgery or childbirth, a scan is done. This identifies retention early, allowing us to manage it promptly and avoid bladder overdistension.

der scans are everywhere in hospitals and clinics to guide urine management. They help us determine if a patient truly needs a catheter, ensure the bladder isn’t overfull, and contribute to safer care by reducing infections.

NHS clinicians, especially nurses, are often trained to do bladder scans at the bedside as part of standard care.

How to Perform a Bladder Scan

Performing a bladder scan is simple when you follow the correct technique. The ideal steps as per the NHS recommendations to do a bladder scan safely include:

How To Do A Bladder Scan

10 minutes

Explain and Prepare

Inform the patient about the procedure and secure their consent. It is crucial to ensure their comfort. Use privacy curtains or close doors to maintain confidentiality and alleviate anxiety.

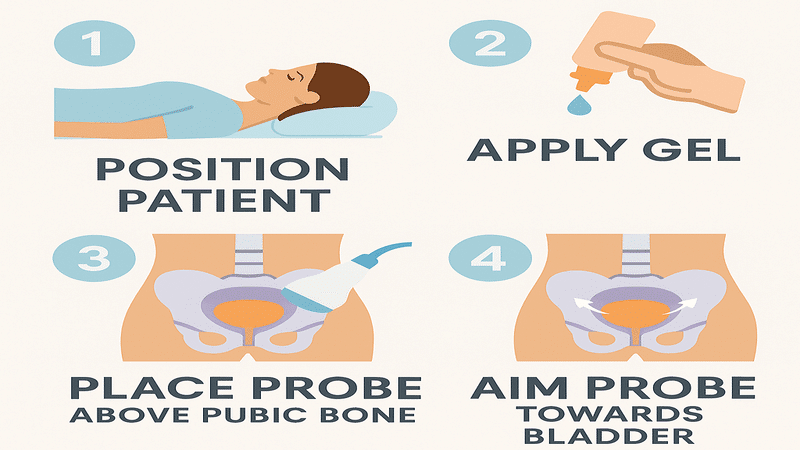

Position the Patient

Instruct the patient to lie on their back (supine position) with their lower abdomen exposed. For added comfort, a slightly raised head position (semi-recumbent) is recommended, but ensure that the abdomen remains flat and relaxed.

Hand hygiene and setup

Wash or sanitise your hands and wear gloves if required. Turn on the bladder scanner device and select the correct patient gender setting. (Most scanners have male/female options to adjust for anatomy. If scanning a female patient who has had a hysterectomy, use the male setting for accuracy.)

Apply gel

Palpate the patient’s pubic bone (just above the pubic hairline). Apply a generous amount of ultrasound gel to the scanner probe or directly on the skin about 3 cm above the pubic bone midline. The gel ensures good sound wave conduction.

Place the probe

Place the probe on the midline about an inch (approximately three finger-widths) above the pubic bone.

Aim the probe slightly downwards towards the bladder (usually angling towards the patient’s tailbone/coccyx). This angle helps centre the bladder in the ultrasound field.

Scan the bladder

Press the “Scan” or start button on the probe/device. Hold the probe steady while the scanner emits ultrasound pulses.

You may see the bladder image or a crosshair target on the screen – some devices guide you to move slightly to find the bladder. Once the scan is complete (often indicated by a beep), the machine calculates the bladder volume.

Repeat for consistency

Many scanners will take multiple readings quickly, or you can repeat the scan a couple of times to ensure accuracy.

If the first reading seems off (e.g. zero when you suspect a full bladder), adjust the probe position or angle and scan again. Typically, obtaining 2–3 consistent readings is recommended for confidence.

Post-scan

Clean off the gel from the patient’s skin and let them cover up or dress. Clean the probe with a disinfectant wipe according to local infection control policy (wipe away gel and sanitise the probe head). Perform hand hygiene again.

Record and interpret the result

Note the volume reading from the scanner (in mL) and document it in the patient’s chart along with the time and any relevant observations (e.g. patient discomfort, whether it was pre- or post-void).

Inform the patient of the basic result; for example, you might say, “It looks like there’s about 300 mL in your bladder now,” and explain the next step.

Most bladder scans in practice are straightforward. The entire process takes only a minute or two once the machine is prepared. Using proper technique—such as correct positioning, adequate ultrasound gel, and appropriate settings—is essential for obtaining a reliable reading.

Interpreting Bladder Scan Results

After the scan, you will receive a volume measurement (in millilitres) indicating the amount of urine in the bladder. However, understanding what these numbers mean requires context.

- Post-void residual (PVR) volume: This is the urine left after the patient has tried to empty their bladder. In healthy individuals, very little may remain. A normal PVR is usually <50–100 mL.

- For example, 30 mL residual is essentially an empty bladder, and 80 mL might be okay in an older adult. Generally, residual volumes greater than 200 mL are considered elevated and indicate incomplete bladder emptying.

- If a patient’s PVR is greater than 200 mL on repeated scans, it may warrant further evaluation or intervention (e.g., teaching double-voiding techniques, adjusting medications, or referring to urology).

- Urinary retention volume: If the patient has not voided at all (acute retention), the scan shows the total volume in the full bladder.

- How much is too much? Many clinicians use a threshold of ~300–500 mL for action. In practice, finding >300 mL in a patient who cannot void or is in pain would justify catheterisation.

- Volumes greater than 500 mL indicate significant retention and a risk of overstretching the bladder; therefore, drain immediately. Always correlate with symptoms: even if the volume is <300 mL, a patient in severe discomfort may still need relief. Conversely, someone with 250 mL who feels fine can be monitored a bit longer. Clinical judgment is key.

- Before versus after voiding: Sometimes scans are performed both before and after voiding. A large pre-void volume (e.g. 400 mL) is not abnormal if the patient then voids most of it.

- It’s the post-void number that indicates whether they emptied properly. So if 400 mL was present and 80 mL remains, that’s a good outcome (320 mL voided).

- But if 400 mL was present and 350 mL remains after “voiding,” that means the patient could barely void – a sign of retention or obstruction.

- Normal Bladder Capacity: An adult bladder typically holds about 400-600 mL comfortably. Patients will usually feel full by ~400 mL.

- Therefore, a scan showing ~100 mL when someone feels full may indicate either a false reading or a bladder sensation issue. Some patients (especially elderly or those with neuropathy) might not feel fullness even at 500 mL.

- Knowing the patient’s baseline and symptoms is crucial for accurate interpretation of their condition.

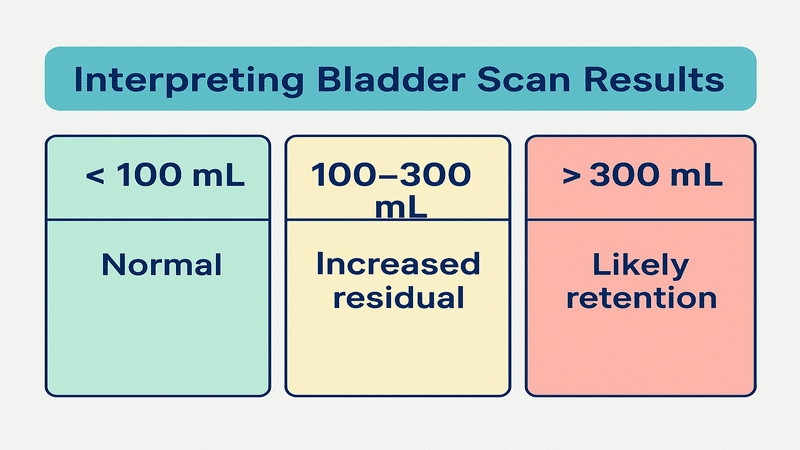

Bladder Scan Normal and Abnormal Ranges

For ease of understanding, here is a quick reference table for bladder scan volumes and their interpretations:

| Bladder Scan Volume | Interpretation & Action |

|---|---|

| 0–50 mL | Essentially empty bladder (normal post-void residual). No action needed. |

| 50–100 mL | Low residual volume. Generally normal, especially in older adults. |

| 100–200 mL | Mild residual. Could be acceptable on occasion, but if persistent, may indicate incomplete emptying. Monitor or encourage better voiding (e.g. double void). |

| >200 mL | Significant residual (incomplete emptying). Repeat scans on different occasions. If consistently >200 mL, consider evaluation (e.g. check for obstruction, bladder scan again later or seek specialist advice). |

| >300 mL (acute retention) | Likely acute urinary retention if patient cannot void. Typically warrants catheterization, especially if patient is uncomfortable. |

| >500 mL | High volume retention. Bladder is very full – prompt catheterization to relieve is usually indicated to prevent harm. |

Note: Always interpret scan results in context. For example, a frail elderly patient with 150 mL residual and recurrent UTIs might need intervention, whereas a young postoperative patient with 150 mL once may be fine with just observation. If residuals appear rising over time or volume of bladder increases, it could mean worsening retention.

Limitations and Special Considerations

There are certain situations where a bladder scan can lose value and give inaccurate results. These include:

- Body habitus: Obesity or excessive abdominal fat can make it more challenging for ultrasound to penetrate and obtain a precise reading. The scanner may underestimate volume in a very obese patient, or you may need to apply slightly more pressure to ensure good contact.* Patient position and movement: The patient should be positioned relatively flat on their back. If the patient is lying on their side or sitting up too much, the bladder may shift and not be in the expected position, leading to false readings. Patient movement during the scan can also cause errors.

- Gender setting and female anatomy: Always use the correct gender setting on the scanner. The presence of the uterus in females can affect the calculation of volume.

- If scanning a female who has had a hysterectomy, set the scanner to “male” mode for better accuracy.

- In pregnant women, bladder scans become unreliable because the enlarged uterus interferes with the ultrasound – volumes may not be accurate, so caution is needed (and if retention is a concern in late pregnancy, direct medical evaluation is advised rather than relying on the scanner).

- Extremely large or small volumes: Most bladder scanners have an upper limit (often around 999 mL) for measurement. If the bladder is massively distended beyond that, the device might max out or give an error.

- Likewise, very tiny volumes (< 10 mL) might read as zero or not register. The policy at one NHS trust notes that volumes over 1000 mL or under 100 mL can result in false readings.

- Use clinical sense – if a scan reads “999 mL” and the patient is in distress, assume the bladder is very full (possibly more than that) and act accordingly.

- Indwelling catheters and devices: Scanning a patient who already has a Foley catheter in place can produce misleading results. If the catheter is patent, the bladder should be empty (scan ~0).

- If you scan and see a volume with a catheter in place, it likely means the catheter isn’t working (either blocked or malpositioned). Also, the catheter itself can cause ultrasound reflection.

- Generally, one would not routinely scan a patient with a functioning catheter except to check for blockage.

- Anatomical anomalies or masses: Conditions such as bladder tumours, large bladder diverticula, or cysts in the pelvis can confuse the scanner’s algorithm.

- The machine assumes that any ultrasound echo-free space is urine in the bladder; therefore, a fluid-filled ovarian cyst or ascites, for example, might be mistakenly counted as part of the bladder volume. * If an “impossible” result occurs (like a massive volume in a patient who clinically doesn’t seem that distended), consider such factors. Always investigate further if readings don’t match the clinical picture.

- User error: Proper technique matters. An incomplete understanding of the device (e.g., failing to aim correctly, applying insufficient gel, or not positioning the probe low enough) can result in a false low reading.

- If you get an unexpected result, double-check your method and try again. Training and practice improve accuracy – many NHS trusts require staff to undergo training before using bladder scanners.

Overall, bladder scans should complement, not replace, clinical assessment. If a patient has a palpable bladder or severe pain and the scanner says “100 mL”, question that result – maybe rescan or use other methods.

Similarly, if scans are consistently borderline high, follow up with appropriate investigations. When used thoughtfully, bladder scanning is a reliable tool, but no test is perfect.

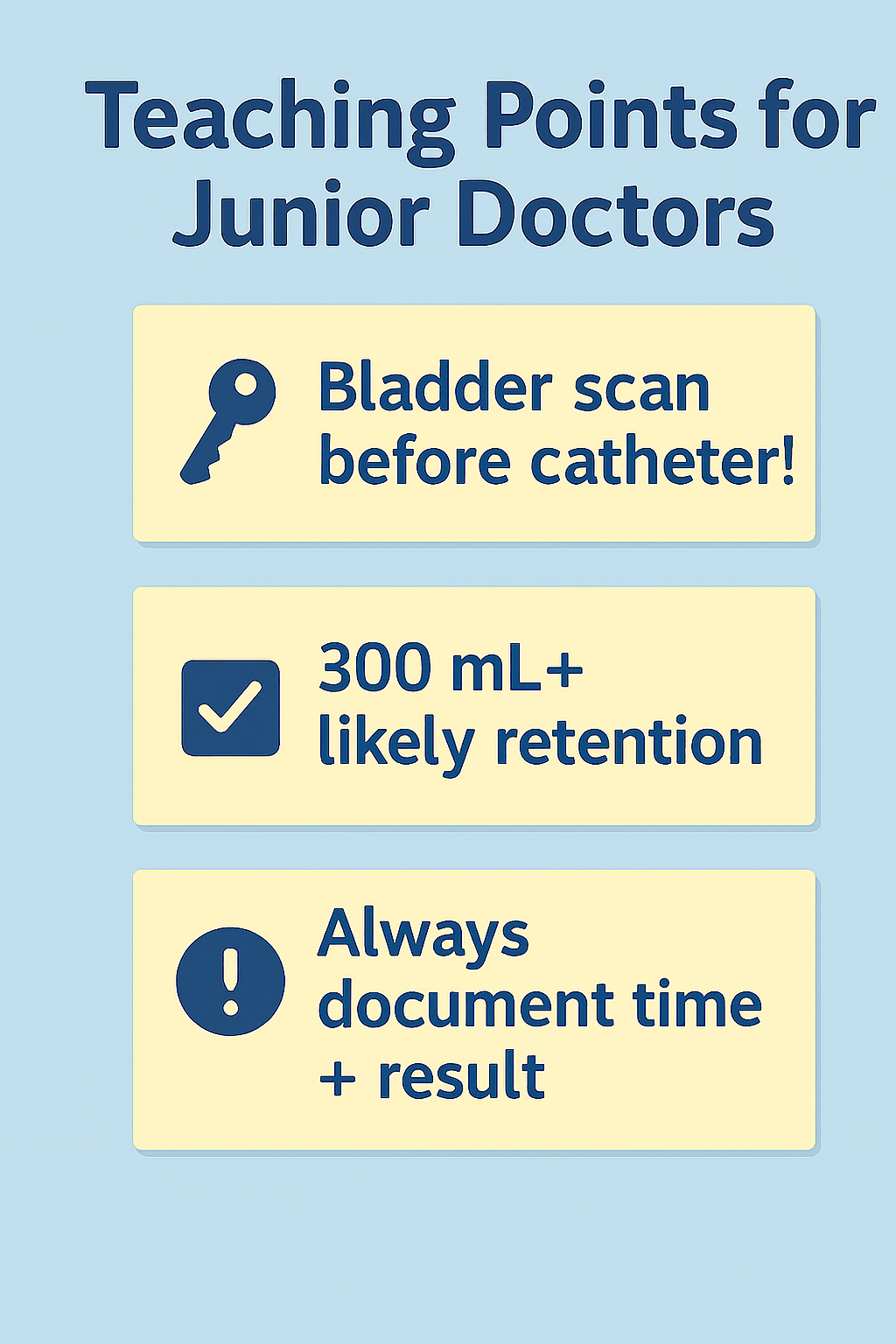

Teaching Points for Junior Doctors

For junior doctors (and new nurses) managing patients with possible urinary retention or related issues, here are some key points to remember:

- Think early: If a nurse calls to report that a patient hasn’t urinated in 8 hours, your first step should usually be to request a bladder scan (if not already done).

- It’s a quick assessment that can guide your next action. Bladder scanning first can prevent an unnecessary catheterisation if the volume is low, or confirm a high volume that needs urgent drainage.

- Threshold for catheterisation: A common practical cutoff is about 300 mL. If the scan shows more than ~300 mL and the patient is uncomfortable or unable to void, it’s generally time to catheterise.

- However, use clinical judgment: even 200 mL can be significant if the patient is in pain and completely unable to void, whereas some patients might manage with 400 mL if slowly draining on their own. Always tailor decisions to the patient’s condition.

- Document and communicate: Record bladder scan results in the notes, including time and whether it was pre- or post-void. If you’re handing over care, mention significant findings (e.g. “He had 450 mL in his bladder, so we put in a catheter”).

- This ensures continuity and ensures that everyone is aware of the plan (for example, when to remove a catheter or repeat a scan).* Know your local protocols: Different wards (e.g. post-surgical, obstetric) may have specific bladder care protocols. For example, a post-op voiding checklist may require a scan if no voiding occurs after 6 hours.

- Be aware of these and manage patients proactively to avoid complications. Ask senior nurses – they are usually familiar with the ward protocols.

- Scanner limitations: Recognise situations where a scan might be misleading. For example, in a patient with ascites or late pregnancy, a direct catheterisation might be needed if retention is suspected, rather than relying on an ultrasound reading.

- Also, if scans are borderline (e.g., ~200 mL residuals but the patient has recurrent UTIs), consider further evaluation (such as formal ultrasounds or a urology referral) even if it’s not an “acute” issue.

- Learn to use the scanner: Take the opportunity to practice using the bladder scanner under the supervision of a trained professional.

- It’s often considered a nursing task, but junior doctors should know how to do it too – it makes you independent on nights or when on calls, when you might be the one assessing a patient. Plus, understanding the process helps you trust (or troubleshoot) the results you’re given.

By keeping these in mind, junior doctors can use bladder scanning effectively in patient management and avoid interventions when not needed.

FAQs

Is a bladder scan the same as a bladder ultrasound?

Yes – a bladder scan is essentially a specialised ultrasound of the bladder. It uses ultrasound waves to visualise the bladder and measure urine volume.

The term “bladder scan” usually refers to the quick bedside test with a portable device, whereas a formal “bladder ultrasound” might be a more detailed exam by the radiology department. But in essence, both use ultrasound technology to look at the bladder.

How accurate are bladder scanner readings?

Bladder scanners are generally accurate for clinical purposes, with an error of ±15 % or less for moderate volumes. However, accuracy can be affected by patient obesity, huge bladder volumes or improper probe positioning.

In ideal conditions, they provide a good ballpark figure (e.g., 50 mL vs. 300 mL vs. 600 mL). Always repeat the scan if the result doesn’t align with the clinical picture, and remember that at extremes (very high or low volumes), the readings are less precise.

What volume on a bladder scan indicates urinary retention?

There’s no single absolute number, but typically, over 300 mL of urine with inability to void would be considered urinary retention that warrants intervention.

Some patients may experience retention with lower volumes if their bladder capacity is small; however, generally, 300–500 mL is considered a red flag range. Chronic retention can occur with moderately high residuals (e.g., 200–400 mL) without immediate pain, but this still signals incomplete emptying.

It’s essential to correlate symptoms with retention: retention is ultimately the inability to urinate when the bladder is full, so any significant volume the patient can’t void is effectively considered retention.

Who can perform a bladder scan in the NHS? Do I need a doctor for it?

Any trained healthcare professional can perform a bladder scan. In the NHS, it’s very common for nurses (ward nurses, continence specialists, etc.) to perform bladder scans as part of their routine assessment.

Healthcare assistants with appropriate training may also perform this task in some settings. Doctors, especially junior doctors, may also perform scans, but often nursing staff will have the machine on the ward and know how to operate it.

No specific doctor’s order is usually required – it can be done based on clinical need and ward protocol.

Are there situations where you shouldn’t do a bladder scan?

Generally, it’s a safe procedure, but there are a few cases where it might not be feasible or practical. If the patient has an abdominal wound or dressing right over the bladder area, you might not be able to place the probe there.

If a patient cannot lie reasonably flat (e.g., due to severe back pain or respiratory issues requiring an upright posture), scanning may be difficult or the results unreliable.

Additionally, as mentioned, the scan’s accuracy is poor in late pregnancy; therefore, a clinical assessment is more critical in this scenario. Lastly, if the patient refuses (i.e., does not consent), you, of course, would not proceed with the scan.

Is a bladder scan painful or risky for the patient?

Not at all – bladder scanning is painless. The patient will feel the cool gel and the probe on their lower abdomen. There’s no insertion into the body and it only takes a short time.

It’s also very safe; it uses sound waves, which have no known harmful effects at the diagnostic levels used.

There’s no exposure to radiation. One of the significant advantages is avoiding the risks associated with catheterisation (e.g., infections or urethral trauma). So it’s a very patient-friendly test.

What if the bladder scan shows a very high volume, like over 1 litre?

Extremely high readings (approaching the scanner’s limit, often around 999 mL) mean the bladder is likely massively distended. In practice, most bladders typically reach a maximum capacity of around 600–800 mL before causing significant pain or overflow. If you ever see a reading like “999 mL” on the screen, treat it as a substantial volume retention.

The exact number might be off, but it’s far above normal. The priority is to relieve the retention (usually by catheterisation) rather than to know the precise volume. After draining, you can measure the urine output to know how much was actually in there.

Also, be aware that the scanner may underestimate when volumes are very high (it might report 500 mL, but the actual volume could be 700 mL). So clinical judgement is essential – if the patient is in distress and scan is high, act to relieve it.

Can a bladder scan detect other problems, such as bladder stones or tumours?

A bladder scan’s primary purpose is to measure urine volume, not to diagnose pathologies. It’s not as detailed as a formal ultrasound. While performing a scan, the device doesn’t provide precise imaging that a clinician can interpret for abnormalities – it just calculates volume.

So you won’t reliably see tumours, stones or other bladder abnormalities on a standard bladder scan machine. Occasionally, if there’s something like a huge bladder stone, it might interfere with the reading, or the machine might have trouble measuring. Still, it won’t specifically tell you “what” is in the bladder.

If a patient is suspected to have bladder stones, tumours or other structural issues, they would need a dedicated ultrasound or cystoscopy for diagnosis.

Do I need to prepare for a bladder scan in any special way?

For the patient, there’s usually no special prep needed. Unlike some ultrasounds, they don’t typically require drinking extra water beforehand, unless the scan is specifically to assess bladder filling capacity. Bladder scans are often done on the spot when needed (e.g. when retention is suspected).

The patient should ideally lie down and expose the lower abdomen, but they don’t need to fast or take any medication.

It’s helpful to know the timing of their last void, as that can help interpret the results (e.g., “300 mL and last void was 2 hours ago” versus “300 mL and they just voided 5 minutes ago” mean different things). For clinicians, ensure the machine is charged and you have gel and wipes – that’s about it.