When I first joined the NHS as a junior doctor, I had a lot of things I wanted to do – Clinical Audit was on my checklist. Despite reading the audit cycle and steps from various sources, I could not understand exactly how to do it.

In this post, I want to share a personal story – my first clinical audit. It’s a friendly, candid account of how I, a junior doctor new to the NHS, conducted a medical audit on constipation management in a geriatric ward.

Along the way, I’ll explain what a clinical audit is, why I chose this topic, how I did it (retrospective data collection from 50 patients), and what I learned.

If you’re a junior doctor or trainee interested in audits, I hope my experience serves as a helpful example of a clinical audit and inspires you to initiate your own quality improvement project.

What Is a Clinical Audit?

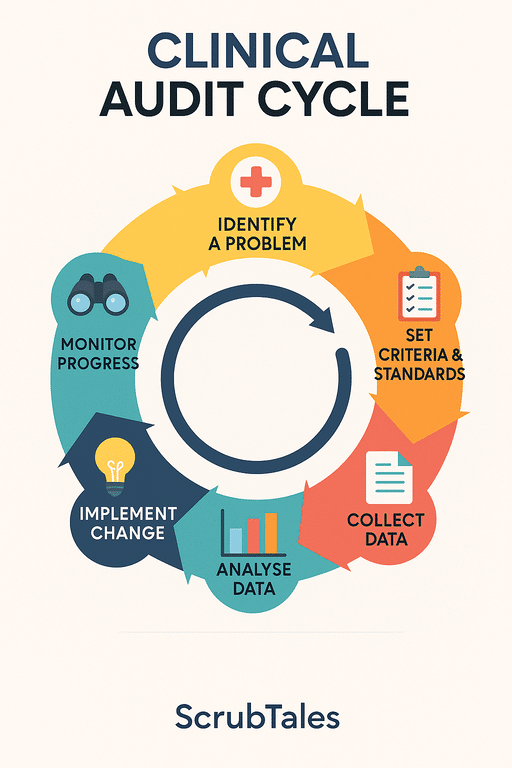

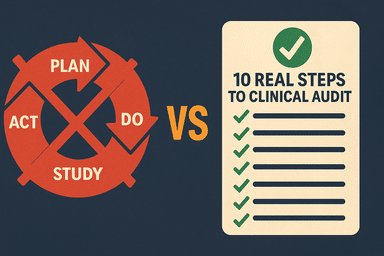

For those unfamiliar with medical audits in healthcare, a clinical audit is a quality improvement process in which healthcare professionals review current practices against explicit standards to enhance patient care.

In simpler terms, we measure what we’re actually doing in practice, compare it to what should be done (based on guidelines or best practice), and then make changes to close any gaps.

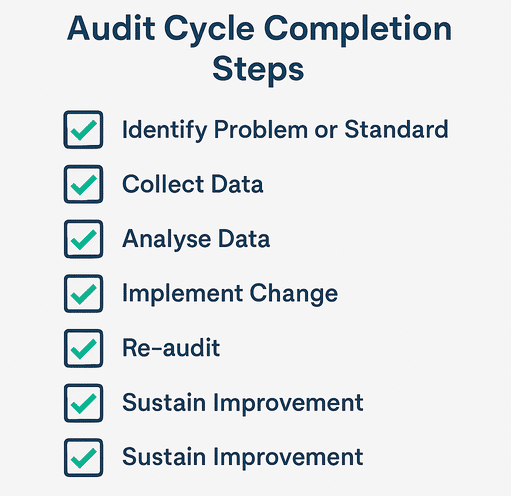

Clinical Audit Cycle: identify a problem ➡️ set standards ➡️ collect data ➡️ analyze gaps ➡️ implement changes ➡️ re-audit.

Unlike research that asks “what is the best thing to do?”, an audit asks “are we doing the right thing, and how can we do it better?”.

In the NHS, clinical audits are a familiar tool for improving quality and safety. (Some countries refer to this as a medical audit, but in the NHS, we use the term’ clinical audit’.)

In a nutshell: A clinical audit in healthcare is about checking if we are following agreed standards and improving care if we are not. It’s one of the key steps junior doctors take in contributing to patient safety and quality improvement.

Every trainee, from foundation doctors to registrars, is encouraged (and often required) to engage in audits. Don’t worry if you’re new – I was too! Below, I’ll walk you through how to do a clinical audit using my recent project as an example.

Do I need any training to do a Clinical Audit?

No! Honestly, you learn by doing it. CPD courses don’t really help, but the NHS offers training if you are interested, especially if you are trying to improve your portfolio – QIP Bronze Training by the NHS.

Why I Chose Constipation (An Overlooked Geriatric Issue)

I decided to focus my medical audit on constipation management in elderly patients. Why constipation? During my geriatrics rotation, I observed that bowel care was sometimes neglected.

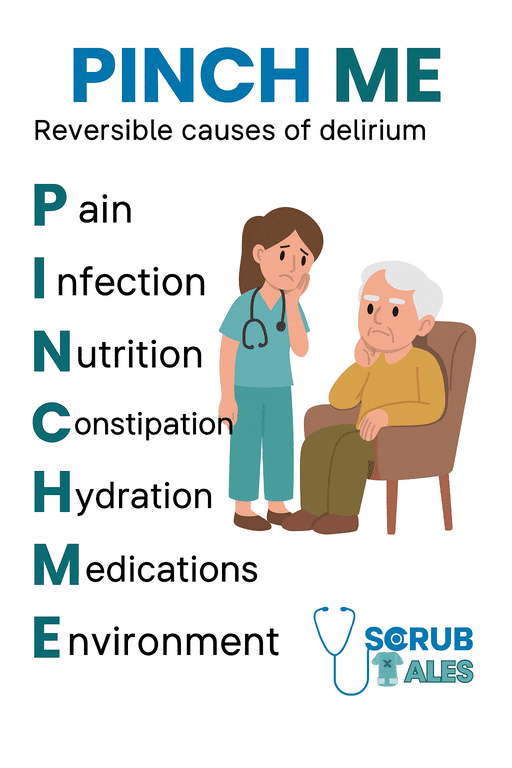

Many of our older patients were on multiple medications (like opioids and antacids) and had mobility issues, putting them at high risk of constipation. Indeed, constipation investigation is part of the PINCH ME mnemonic, you know, for the confusion screen.

Yet, documentation about their bowel habits was inconsistent, and interventions were often delayed until patients were very uncomfortable.

One memorable case was an elderly gentleman who became confused and agitated; it turned out he hadn’t opened his bowels in a week – severe constipation was contributing to his delirium!

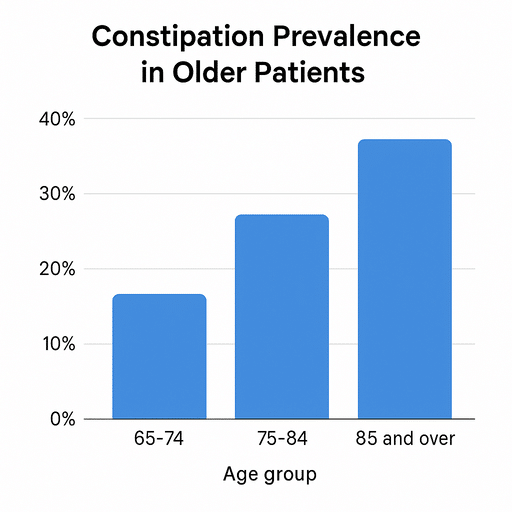

Constipation might not be a glamorous topic, but it’s incredibly important in geriatrics. Studies report that anywhere from about 15% up to 60% of acutely hospitalised patients experience constipation.

That’s huge! If we don’t manage it well, it can lead to pain, faecal impaction, bowel obstruction, or worsening confusion in vulnerable patients. On the flip side, proper constipation management (like timely laxatives and monitoring) can greatly improve a patient’s comfort and prevent complications.

With the support of my consultant and audit lead, I formulated a plan to audit how well our ward was managing constipation in accordance with national guidelines.

Honestly, I saw this as an opportunity to learn the NHS way of doing things – including navigating the clinical audit cycle and enhancing my practice.

Plus, I had a personal motivation: I wanted to ensure our patients didn’t suffer silently from something as treatable as constipation.

Realistic Step-by-Step: How I Actually Did My Clinical Audit

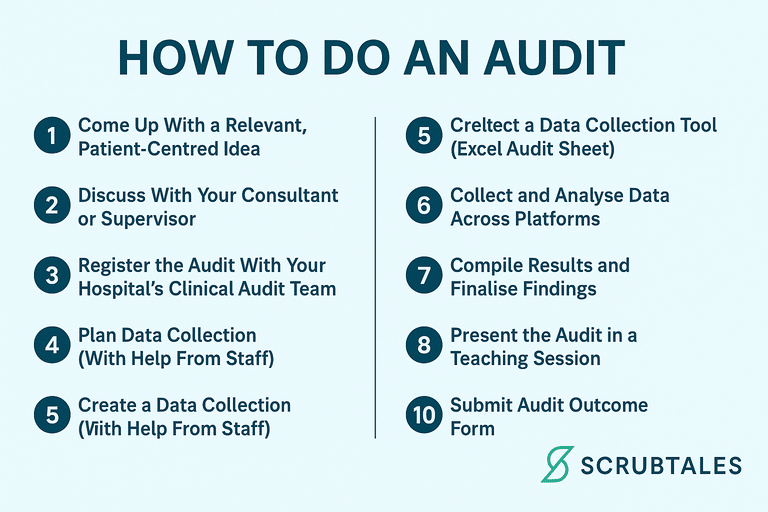

The problem with clinical audits is that no one tells you exactly how to do them. What are the real steps? How do I register? How do I gather data? No one tells you that but the audit cycle. (P.S.: Audit leads are super supportive if you reach out to them.)

Let’s be real – clinical audits don’t magically happen. Here’s a practical breakdown of how I did mine from idea to presentation:

How To Do an Audit in the NHS

1. Come Up With a Relevant, Patient-Centred Idea

I noticed constipation was a common and poorly documented issue in elderly inpatients. It wasn’t flashy, but it mattered – especially in geriatrics.

This idea can emerge anywhere you work, for any aspect you want to improve, or for anything you notice that is worth improving. Do not conduct a clinical audit solely for the sake of a portfolio; this is a common practice, and there is often poor reflection afterwards (consider how you would answer this in your IMT or job interview).

2. Discuss With Your Consultant or Supervisor

I floated the idea with my consultant, who encouraged me and offered to supervise. It’s always beneficial to have a senior backing the audit – they’ll help refine the scope.

Plan how many patients you will audit, the method (retrospective or prospective) you will use, which wards or areas you will cover, what your criteria will be, and what guidelines you will use as standards – this can be local or national, such as NICE guidelines.

Ensure that your criteria are outlined in the guidelines and that you have a reasonable number or percentage to set.

3. Register the Audit With Your Hospital’s Clinical Audit Team

Every Trust has a formal process. I completed the MSE Clinical Audit Registration Form (Part I), outlining the aim, methodology, and standards.

They are very friendly and helpful and will guide you in any issue you face. They are easily reachable and available.

4. Plan Data Collection (With Help From Staff)

I gathered case numbers and patient records with help from:

1. Admin staff (for inpatient lists),

2. Ward nurses (for patient notes and stool charts),

And myself (digging into records). Sources included:

1. DAT book

2. EPMA (medication history)

3. PatientTrack (stool charts)

4. Scanned paper notes from the portal

5. Discharge summaries

5. Create a Data Collection Tool (Excel Audit Sheet)

I designed a spreadsheet with criteria, targets, and a “yes/no” format for each patient. This became my go-to audit tracker.

6. Collect and Analyse Data Across Platforms

Reviewing:

1. Drug charts

2. Stool charts

3. Medication charts

4. Admission notes

5. Bloods (for complications)

6. Discharge summaries

This took time, but gave the full picture. I recorded everything in the Excel sheet, which was my primary clinical audit tool.

7. Compile Results and Finalise Findings

Once I had data from 50 patients, I calculated percentages and compared them against my targets. Spoiler: we had a lot of room for improvement.

8. Discuss the Results With Consultant and Team

I presented my findings to my consultant. We brainstormed simple, impactful changes that didn’t need massive system overhauls.

9. Present the Medical Audit in a Teaching Session

I delivered a brief teaching on the audit findings, what we did wrong, and how we’re addressing the issues. Staff were surprisingly engaged – a few even said “I never thought of documenting that before!”

Note that you will not get the audit certificate if you do not present your audit findings. Not only for presentation, but the attendees also contribute to developing recommendations as the next steps for the clinical audit.

Note that audits also support your crest form and help you gain favour from your consultant.

10. Submit Audit Outcome Form

This was the Part II form to close the loop. I included:

1. Audit results (e.g. % who had normal bowel habits documented!)

2. Action plan (board round prompts, staff training, printed guidelines)

3. Signatures from my supervisor and audit lead

Once I submitted, I received the certificate in no time. I am currently planning to undertake the second cycle, which I will change to QIP, as this will enable me to earn the full 4 points for IMT.

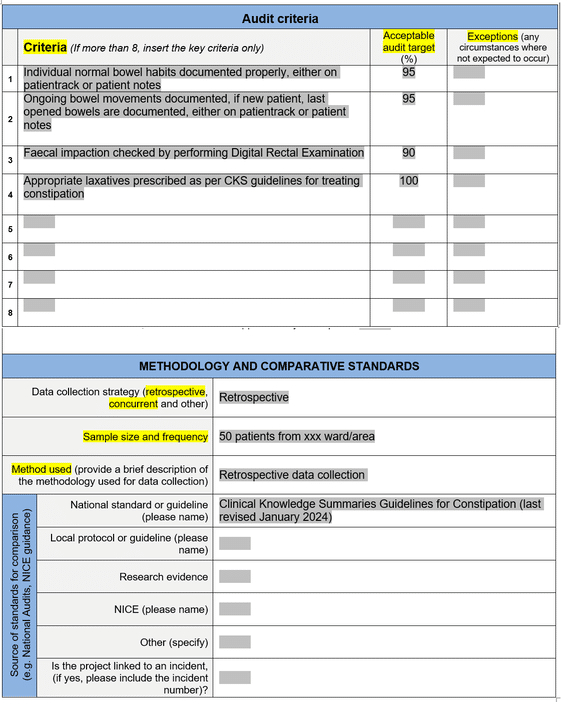

Planning the Audit – Standards and Criteria

Once I had my topic, it was time to plan the audit. This involved clarifying exactly what I would measure and what the “gold standard” I’d compare against.

In the NHS, most audits begin by setting criteria (the aspects of care to be assessed) and standards (the target level of care or compliance to be achieved, usually derived from guidelines).

I followed the hospital’s audit registration process, which meant filling out a form detailing my audit aim, methodology, and criteria. It felt a bit daunting at first, but my supervisor and the clinical audit department were very helpful in refining the project.

Standards: I turned to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS) guidelines on constipation (NICE is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which offers evidence-based guidance).

Note that CKS do not count as guidelines and hence, I had to change the title of my audit after recommendations from the clinical audit lead.

According to NICE and best practice, good constipation management in adults – especially the elderly – should include:

- Documenting the patient’s normal bowel habit (on admission) and ongoing bowel movements during the hospital stay.

- Checking for faecal impaction with a digital rectal examination (DRE) when impaction is suspected (for example, if a patient hasn’t opened bowels for several days or has abdominal fullness).

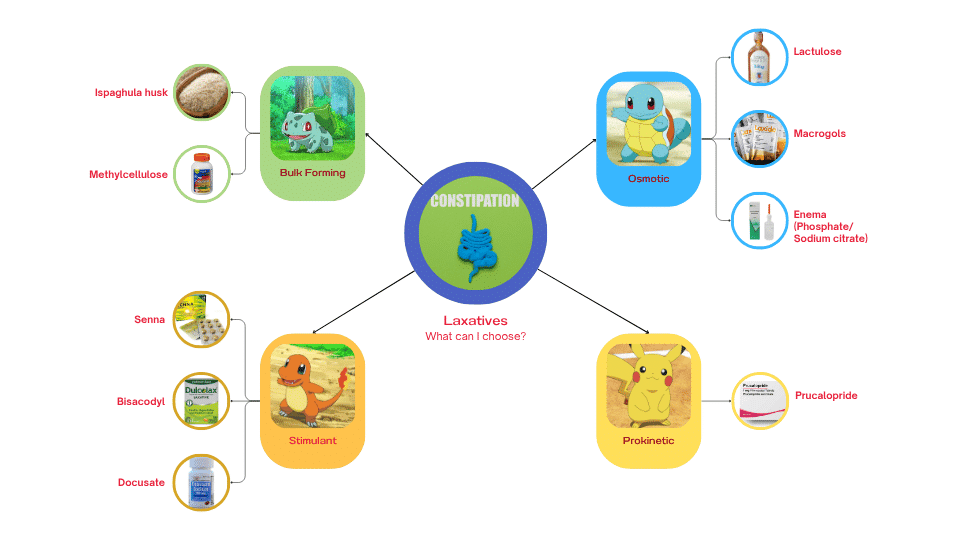

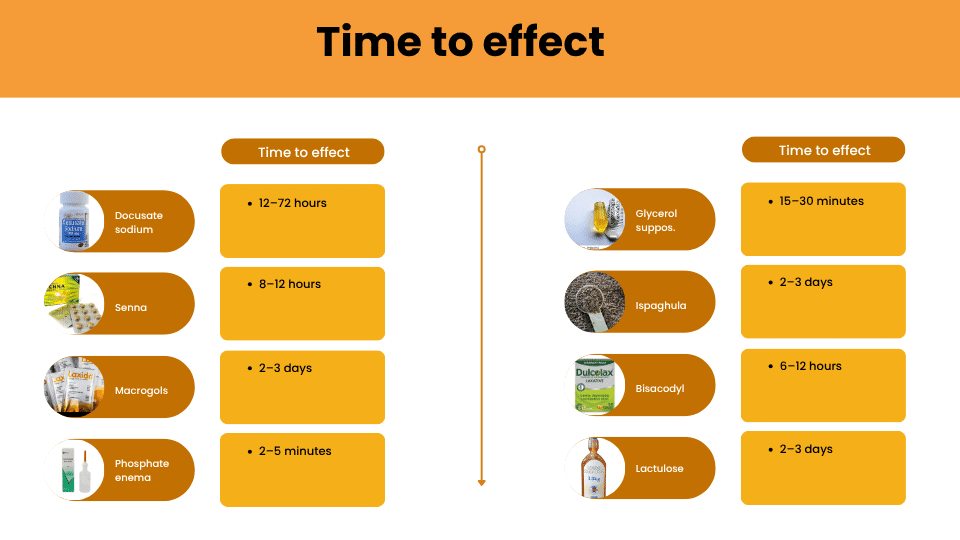

- Prescribing appropriate laxatives as per guidelines (e.g. stool softeners, osmotic or stimulant laxatives as needed, rather than just leaving the patient or using something ineffective).

Using these, I set three key audit criteria. For each criterion, I also set a target compliance rate (usually aiming high – 90-100% – as these are standards of good care). Here’s a summary of the audit criteria and the targets I decided on:

| Audit Criterion | Target (% compliance) |

|---|---|

| Bowel habits documented (on admission and daily) | 95% |

| DRE is performed if faecal impaction is suspected | 90% |

| Appropriate laxative prescribed per NICE CKS guidelines | 100% |

Table: Audit criteria and target compliance levels. I set ambitious targets (close to 100%) since every patient should ideally receive this aspect of care if needed.

Aiming for 95-100% might sound strict, but if you think about it, these are basic care standards. There aren’t many valid exceptions – for instance, every inpatient’s bowel habit should be noted (unless they refuse to discuss it), and any patient with possible impaction should get a DRE (unless contraindicated). High targets set the bar for optimal care.

Data Collection: 50 Patients and an Excel Tracker Tool

With my criteria defined, I proceeded to data collection – the detective work. I chose a retrospective audit design, which involves reviewing patient records from the past.

I selected 50 randomised patients from our geriatric ward over a two-month period. I gathered data from various sources: patient notes, our electronic health record (for medication charts and daily nursing notes), and a system called PatientTrack where nurses record bowel movements.

Note: You cannot select the patients according to you, you have get randomised patients. Patients who cannot be fit in the audit are counted as excluded and should be included in clinical audit results and presentation.

For each of the 50 patients, I collected information on the audit criteria. Essentially, I made a little checklist for each patient:

- Was their usual bowel habit documented on admission? (Yes/No)

- Were ongoing bowel movements charted each day? (Yes/No/Not applicable – e.g., if they stayed <24h)

- If they became constipated or hadn’t opened bowels for >3 days, was a DRE done to check for impaction? (Yes/No/Not applicable – e.g., no signs of constipation)

- If they were constipated, were appropriate laxatives prescribed according to guidelines? (Yes/No/Not applicable)

To stay organised, I used a simple clinical audit tool in Excel. I created a spreadsheet with each patient as a row and the criteria as columns, marking ticks and crosses. This made it much easier to tally up results later.

Using an audit template like this not only saved time but also reduced errors in data gathering. Furthermore, the results will be populated automatically once you enter the data on the second sheet.

I have to admit, collecting data was a bit tedious at times – flipping through notes at 5 pm after ward rounds, deciphering handwriting, and cross-checking multiple systems.

But it was also eye-opening. As I reviewed each case, I began to notice patterns. For example, I noticed that documentation of bowel habits was often present on admission notes if a senior nurse prompted it, but sometimes junior doctors (including myself!) forgot to ask.

I also noticed that when patients were seen by certain diligent nurses, their bowel charts were immaculate, whereas others had gaps. This on-the-ground observation was already giving me ideas for improvements even before I ran the numbers.

Finally, with data on 50 patients, I analysed the results. I was both excited and a little nervous to see how our ward was doing. After tallying the data in my Excel sheet, I calculated the compliance percentage for each criterion.

For obvious reasons, I cannot reveal the data regarding the clinical audit. But audits often reveal things we suspect anecdotally but now have proof of. The good news is that identifying these shortfalls is the first step to improving them.

On the bright side, the very act of doing this audit raised awareness. While collecting data, I had informal chats with colleagues – for instance, mentioning to a junior doctor that “Hey, I noticed we often don’t document bowel habits; I’m auditing that and it’s looking low.”

Even before the audit presentation, people started to realise this was an issue. In that sense, the audit was already catalysing change.

Turning Results into Action – Closing the Loop

A clinical audit is only as good as the action it inspires. The phrase “closing the loop” is often used; it means using the audit findings to implement improvements and then re-auditing to see if those improvements were effective (thus completing the audit cycle).

After crunching the numbers, I compiled a short report and discussed the findings with my supervisor. We then presented the audit at our department meeting. Presenting as a junior doctor to a room of seniors was nerve-wracking, but I kept it simple and solution-focused.

Have a look at how the first slide of my presentation looked:

Here are the changes we decided to implement as a result of the audit:

- Improve documentation: To achieve this, we came up with training the staff, especially nursing staff and HCAs, as they are the ones who do the Bristol charting or the poop type charting for the patients admitted in the ward. Small sessions were delivered.

- DRE training and reminders: Recognising that DREs were being done infrequently, we conducted a quick refresher session for junior doctors on how and when to perform a digital rectal exam in suspected constipation. However, the main point was repeatedly emphasised.

- Laxative prescribing protocol: We identified a need for a generic trust guideline, and this was drafted (although a painful and lengthy process, not recommended). This set the new standards for the outcome of the first cycle of the audit.

Have a look at something really cool I designed regarding laxatives:

None of these interventions are rocket science – they’re practical steps, mostly about better communication and using existing best practices more reliably.

But that’s the beauty of clinical audit: by shining a light on a problem, you motivate the team to adopt solutions that were often known but not consistently applied.

We planned to re-audit after ~6 months to see if these changes improved our metrics (that would be the final step of the audit cycle).

Spoiler alert: I haven’t done the full re-audit yet (that’ll be a story for another day), but early signs are positive. The nurses tell me the bowel charts are more consistently filled, and I’ve noticed colleagues referencing the constipation protocol when writing up laxatives. Even I have changed my practice – I’m far more conscious now to ask about bowels and not shy about doing a DRE if needed.

Reflections and Lessons Learned

From this clinical audit journey, I learned a great deal – not just about constipation, but also about the process of improving care as a junior doctor.

Although overwhelming as I was simultaneously preparing for MRCP 1, I still survived. Here are a few personal reflections:

- Audits aren’t just tick-box exercises: Initially, I undertook an audit partly because it’s required for my IMT. But I was pleasantly surprised by how engaging it became.

- When you choose a topic that matters (such as an everyday problem causing patient distress), the audit feels more meaningful. I found myself invested in the outcome because I knew it could help patients and our ward team.

- In the end, it wasn’t about just getting an audit on my CV – it was about making a small positive change in my workplace.

- Teamwork is key: Even though I led the audit, it was a team effort. I received support from my consultant supervisor, a registrar who helped refine the plan, nurses who kindly assisted me in locating notes and answered my numerous questions about where documentation is stored, and a fellow junior who helped double-check some data.

- Engaging the whole team early – even just by chatting about what I was doing – created buy-in. By the time I presented the results, no one was defensive; instead, people were eager to fix the issues.

- It taught me that quality improvement in the NHS is a collaborative sport, not a solo performance.

- Data doesn’t lie (but it can surprise you): I had hunches that documentation was lacking, but seeing the actual numbers was powerful.

- It gives you and the team a clear mandate: “We have to do better.” It also busts any assumptions – for example, I assumed we were probably 80-90% complete on documentation and was surprised to find it was a lot less than that. Now I trust doing the measurements more than my gut feeling.

- Closing the loop takes persistence: After presenting the audit, I realised that making change is one thing, but ensuring those changes stick is another.

- We had to follow up on whether people were using the new protocol, and I’ll need to re-audit to truly complete the cycle. Real improvement is a continuous process.

- As a junior doctor with rotating posts, I also learned the importance of handing over audit findings – I’ve briefed the next junior doctors taking over on our ward to keep the momentum. Quality improvement is an ongoing process, and sometimes you pass the baton.

- Personal development: On a personal note, this project helped me develop skills in project management, data analysis, and leadership (yes, even as a junior doctor, I felt I was leading a mini-project!).

- It also boosted my confidence – if you had told me a year ago I’d stand in front of a room of NHS staff talking about bowel movements, I’d have laughed.

- But here we are! And now I encourage my peers to dive in and try one. It’s one of the best ways to understand and improve the system in which we work.

- In addition to an audit, I also completed an ALS course during the same period that I began my on-call duties.

Tips for Doing Your Own Clinical Audit

If you’re a trainee doctor thinking about doing a clinical audit (NHS or elsewhere), here are some friendly tips and takeaways from my experience:

- Pick a topic that matters to you: Audit something that piques your interest or annoys you on the wards. It could be a clinical audit of hand hygiene, prescribing errors, discharge summaries, or any other relevant area.

- If you care about the topic, you’ll be more motivated, and that enthusiasm will spread to your team.

- Use guidelines to set standards: Always anchor your audit to explicit criteria from reputable guidelines (e.g., NICE guidelines, local hospital protocols).

- This gives your audit credibility and clear targets. Ask, “What is supposed to happen for these patients?” – those become your audit standards.

- Keep it simple and focused: Especially for a first audit, don’t over-complicate it. Limit to a few key criteria (my audit had three). A narrow focus makes data collection easier and the message clearer. Remember, you can’t fix everything at once.

- Plan and utilise tools: Follow the clinical audit cycle step by step – planning, data collection, analysis, action, re-audit. Plan how you’ll get data (which notes, which database).

- Use an audit template or tool, such as a spreadsheet or checklist, to systematically collect data. This helps avoid getting overwhelmed or lost in paperwork. (Feel free to grab the free Excel clinical audit tool I mentioned – it’s a useful template for any audit data collection.)

- Involve others and communicate: Let your seniors and the multi-disciplinary team know about your audit early. Often, they’ll give great suggestions or even a hand with data.

- Additionally, changes are typically implemented by teams, not individuals – so obtaining buy-in is crucial. Don’t be afraid to ask questions like “How do we usually do X?” – you might uncover unwritten practices that need addressing.

- Be ready to implement change: Once you have results, be solutions-oriented. Audit isn’t about blaming, it’s about improving. Think of practical interventions (training, new forms, checklists, reminders) that can help.

- Discuss with your supervisor or team what’s feasible. This is the most rewarding part! Seeing a new process or habit form as a result of your audit gives real meaning to the numbers you’ve crunched.

- Present and share: Present your findings in a clear and concise manner – using charts and concise bullet points helps. Do not hesitate to put your clinical audit project in your TRAC jobs application as well.

- Share the success (or shortcomings) honestly. Most people appreciate the effort and will be on board to improve once they see the data. Also, presenting an audit is good for your portfolio and confidence.

- Close the loop: Plan a re-audit after the changes have been implemented. This might be done by you or future trainees. It completes the cycle and indicates whether the interventions were effective.

- Even if you rotate out, leave a note or handover for someone to re-audit. Quality improvement is iterative – it’s okay if targets aren’t met on the first round, it just informs the next round.

- Keep records: Maintain a folder of your project plan, data, analysis, and action plan. Not only is this helpful for writing it up (or if you want to publish/present at a conference), but it’s also great reflection material for your ARCP or job interviews.

- It demonstrates your commitment to improving care.

These tips are just a starting point. Every audit will teach you something new. Don’t be afraid to dive in – how to do a clinical audit becomes much clearer once you actually start one.

And trust me, if I (as a busy junior doctor) could manage an audit alongside on-calls and clinics, so can you!

Conclusion: A Small Audit, A Big Difference

My journey through this clinical audit on constipation management has been incredibly fulfilling. It began as a simple question – “Are we doing this right?” – and culminated in tangible changes to our ward practice.

Along the way, I learned about teamwork, the importance of data in healthcare, and how even junior doctors can drive improvements in the NHS.

This experience showed me that audits aren’t just bureaucracy or a line on a CV; they are powerful tools in the NHS for ensuring our patients receive the best care possible.

For my geriatric patients, the difference is real: better comfort, fewer days of discomfort or delirium from untreated constipation, and a team more alert to their bowel needs

For me, I’ve gained confidence and skills – and a fair bit of new knowledge about managing constipation! It’s also broken the ice for me to pursue more audits and quality improvement projects in the future.

I hope you found my clinical audit story informative and maybe even inspiring.

If you’re a junior doctor or new to the NHS, finding your feet in the NHS, remember that getting involved in audits and QI projects is one of the best ways to understand the healthcare system and contribute positively.

It’s normal to feel unsure how to start, but hopefully this example has demystified the process a bit.

I am unsure if you actually reached this part, but if you did, I would love to see a comment or a feedback below!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can I do a clinical audit during a clinical attachment?

Yes, you can—if you have the support of a consultant. Many IMGs use clinical attachments to get audit or QI experience.

You’ll need a willing supervisor, access to anonymised patient data, and formal registration through the audit department.

👉 Here’s how to write a clinical attachment cover letter if you haven’t secured one yet.

Do I need GMC registration to do a clinical audit?

No. While GMC registration helps with access and documentation, you can participate in audits during clinical attachments, observerships, or research roles—as long as you’re supervised and don’t perform clinical tasks.

Can an audit count towards my portfolio even if I’m not in a training post?

Absolutely. Even if you’re in a non-training job (e.g. clinical fellow, LAS, or trust-grade), clinical audits count toward your NHS portfolio and strengthen your application for training posts like IMT or GP.

How is a clinical audit different from a quality improvement project (QIP)?

A clinical audit compares current practice to a defined standard (e.g. NICE guidelines).

A QIP is broader—it aims to improve care without necessarily comparing against a specific benchmark. Both are valuable; audits are more structured, while QIPs are often more flexible and iterative in nature.

Can I publish or present my audit at conferences?

Yes—many national and international conferences accept clinical audit abstracts, especially those involving real change. Be sure to get approval from your supervisor and the Trust’s clinical governance team before submission.