It happens frequently that as a junior doctor or a nurse, you encounter confused patients either in A&E or wards (especially geriatric wards) and you have to do a complete workup for these patients.

Often, you find yourself struggling with the lists of bloods and tests and screening tools to use for confusion screen workup. While delirium is often common, understanding the necessary steps to be taken is required from you to reflect as safe doctor.

Delirium (acute confusion) is an acute, fluctuating disturbance in consciousness, attention, cognition, and perception. It is very common yet often missed: roughly 1 in 5 hospital patients over 65 has delirium at any time, and up to 60% of cases are unrecognized by frontline staff.

Early recognition is vital because delirium is usually reversible if you find and treat the underlying cause.

This post provides a clear, stepwise approach – from identifying common causes to using screening tools, ordering initial tests (confusion screen bloods), and knowing when to get extra help.

Initial Investigations: The Confusion Screen

When you see a confused patient, you immediate need to rule out delirium vs dementia. This warrants further investigations to find the underlying cause.

Confusion screen includes a panel of basic tests raning from blood tests, CXR, urine mc&s and screening tools like 4AT.

Following are the investigations a junior doctor clerking a patient during on call or seeing a patient in the ward or other settings:

Confusion Screen Blood Tests

- FBC (infection, anaemia)

- U&E (urea & electrolytes for dehydration or renal issues)

- LFTs (liver failure, encephalopathy)

- CRP (infection/inflammation marker)

- Glucose (high or low sugars)

- Calcium (high calcium can cause confusion)

- TFTs (thyroid function tests for metabolic imbalance)

- Vitamin B12 & folate levels (low B12 can cause cognitive changes)

Other Tests

1. Urine dipstick and Urine MC&S

Perform a urinalysis (dipstick) and send urine for MC&S (microscopy, culture & sensitivity) as part of confusion screen if infection is suspected.

If you have passed your MRCP 1 already, you will know why even basic tests are important for investigation delirium.

Trust me, UTIs or urinary tract infections are very common causing delirium in the elderly.

Note: In patients >65, a positive dipstick alone can be misleading (asymptomatic bacteriuria is common), so clinical correlation is key – but any suggestion of UTI in a confused patient warrants culture and likely empiric treatment if febrile.

2. Imaging

- CXR

- A Chest X-ray is the first thing you need to do look for chest infections (pnuemonia) or even heart failure as both can cause confusion and hence CXR forms an integral part of confusion screen.

- CT Head

- If there is any history of head injury, fall, new focal neurological deficits or even when no obvious cause of delirium is found, consider an urgent CT Head. Elderly are prone to falls, and sometimes history will not match, even though there was head trauma.

Don’t scan every confused older person routinely – but go for it if you are worried and need to rule out intracranial injury.

3. ECG

It is good idea to establish baseline as well as look for arrhythmia. AF are fairly common in the UK. Furthermore, you can also spot QT prolongatation or ST changes if any or even electrolyte abnormalities such as peaked T waves in hyperkalaemia.

4. Other Tests

- Blood cultures for sepsis screen

- ABG if you are suspecting CO2 retention in a known COPD patient (easily missed)

- Tox screen for drug levels such as lithium, digoxin or if overdose or toxicity is suspected

- Lumbar puncture is warranted if meningitis or encephalitis is suspected

Delirium Screening Tools: 4AT, CAM, and SQiD

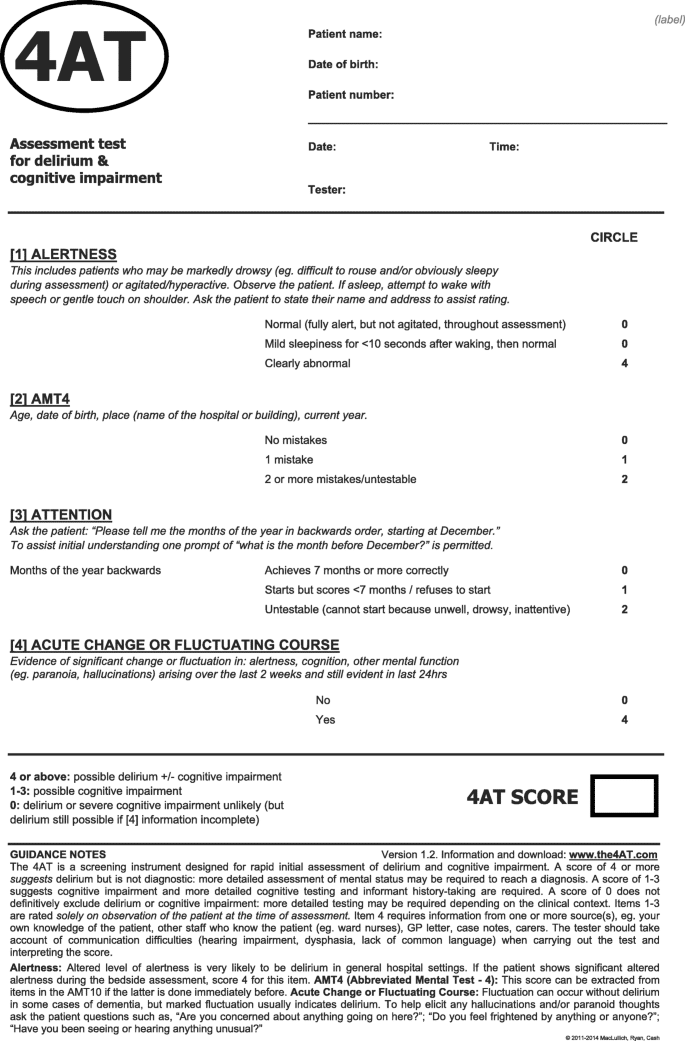

We often come across different tools for confusion screen in the NHS as per the trust but most commonly used are 4AT, CAM, and the “Single Question in Delirium” (SQiD).

Early identification of delirium is crucial. Besides clinical judgment, we have validated screening tools to quickly assess confusion in hospital.

Each has its role – the table below compares different delirium screen tools, including pros/cons and when to use each:

| Tool | Pros | Cons | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4AT (4 ‘A’s Test) – brief test of Alertness, Abbrev. Mental Test-4, Attention (months backward), & Acute change. A score ≥4 suggests delirium. | – Very quick (~2 minutes) to administer – No special training required to use – Validated with high sensitivity & specificity in many settings – Can be done even if patient is drowsy or non-verbal (untestable items score toward delirium) | – Does not differentiate delirium vs dementia on its own – collateral history still needed for acute change – A positive screen (>4) indicates possible delirium but isn’t a final diagnosis (needs clinical confirmation) – Relatively new (some staff may be more familiar with CAM historically) | – Frontline screening tool for acute confusion screen recommended by NICE for general hospital use (e.g. in ED admissions, acute wards). – Use at initial assessment of any confused patient, or if delirium is suspected. – Can repeat daily to track delirium improvement or if new confusion develops. Not for very frequent (hourly) monitoring. |

| CAM (Confusion Assessment Method) – an algorithm-based assessment of delirium (features: acute onset & fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, altered consciousness). | – Well-established with high accuracy in research settings (sensitivity ~94%, specificity ~90% in studies). – Widely used historically; considered a “gold standard” for delirium identification in many studies. – CAM-ICU variant exists for ventilated ICU patients (non-verbal). | – More time-consuming than 4AT (requires a formal cognitive exam to assess attention and thinking). – Training is required for reliable use – proper scoring depends on doing a brief cognitive test and understanding the CAM algorithm. – May be less practical in a hectic ED setting without trained staff. | – Often used by geriatrics or psychiatric liaison specialists or in research. – Can be used for a more detailed assessment if 4AT is positive or if staff are trained in CAM. – Less commonly used on front-line in UK since 4AT’s adoption (CAM is now secondary to 4AT in general wards). – ICU: The CAM-ICU is standard in critical care for intubated or non-communicative patients. |

| SQiD (Single Question in Delirium) – one yes/no question to someone who knows the patient: “Do you feel [patient] has been more confused lately?” | – Extremely quick and easy – literally one question to a relative or nurse. – No training needed; leverages informant’s knowledge of patient’s baseline. – Good specificity (~89%) – a “Yes” strongly suggests a change in mental state. | – Not very sensitive (~44%)– a “No” answer doesn’t rule out delirium (patient could still be delirious even if informant hasn’t noticed). – Depends on having an informant who knows the patient’s normal mentation. – Positive SQiD is not a diagnosis – it’s a prompt for further assessment, not a standalone test. | – Used as an initial screening question on admission or rounds: e.g. ask the family or the nurse, “Does this patient seem more confused than normal?”. – Often built into routine assessments (for example, the **“New Confusion” check in NEWS2 or nursing handovers is akin to SQiD). – If SQiD is “Yes”, it should trigger a formal delirium assessment (e.g. do a 4AT next). – Can be asked daily to monitor for any new confusion in at-risk patients. |

Common Causes of Confusion (Delirium) in Hospital

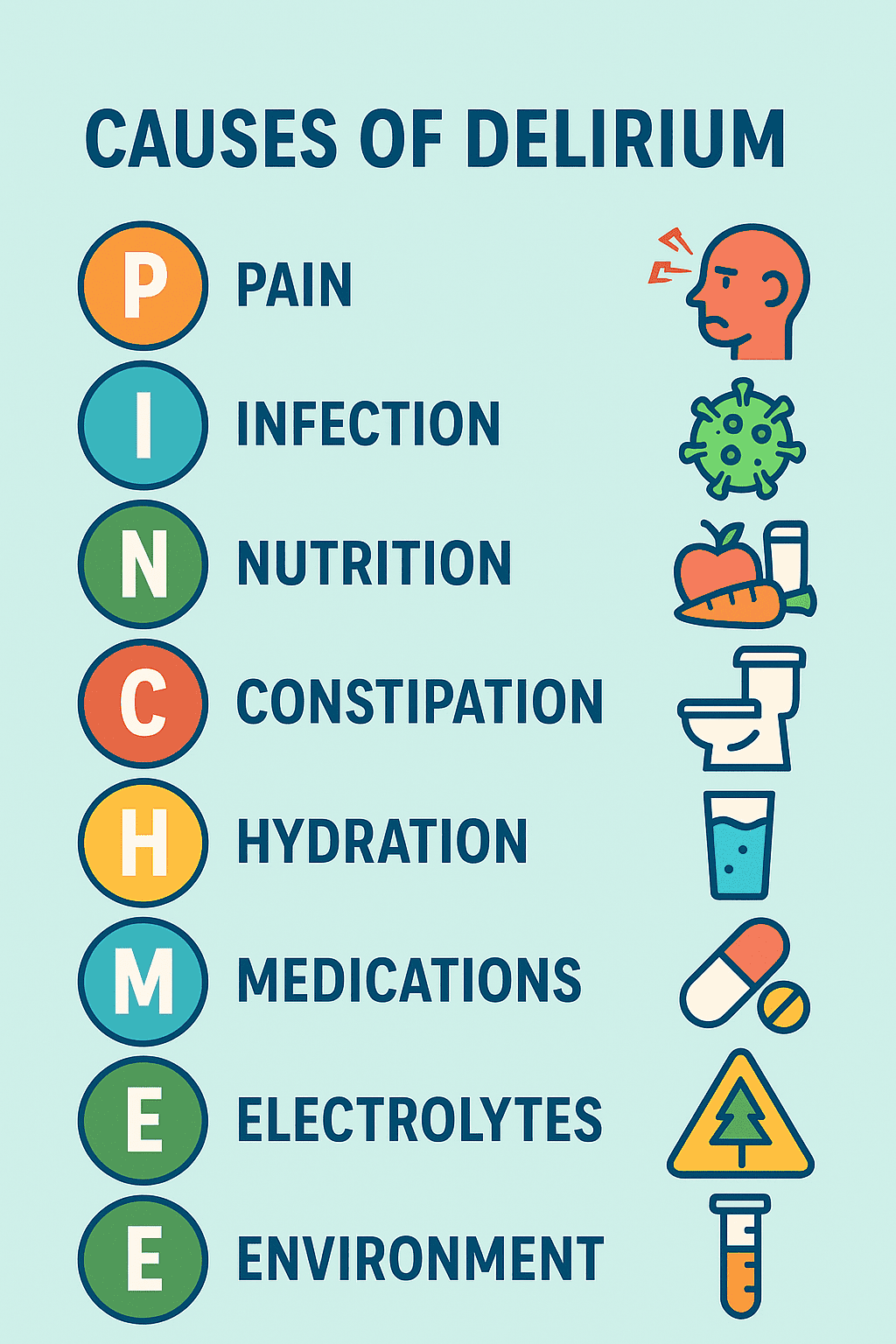

We all come across a very common mnemonic ‘PINCH MEE’ while working in the NHS. This can help you exclude causes of delirium you should be suspecting as often multiple contributing factors are present.

Always rule out the causes before simply saying underlying dementia is the cause for confusion in the elderly. Even so, you will have to do complete acute confusion screen regardless.

- Pain: Uncontrolled pain (e.g. from fractures, ischemia, postoperative pain) can precipitate confusion. Always assess for pain (even in non-verbal patients) and treat adequately.

- Infection: Any infection can cause delirium – common culprits are UTIs, chest infections (pneumonia), sepsis, and others like biliary or skin infections. Sepsis is a must-not-miss cause of new confusion and should be investigated with confusion screen.

- Nutrition: Malnutrition or low blood sugar can contribute. Also consider vitamin deficiencies (e.g. thiamine in alcohol misuse, or B12/folate over longer term).

- Constipation (and urinary retention): Either can cause or aggravate delirium, especially in the elderly. A loaded bowel or distended bladder is an easily treatable cause – check and relieve if present.

- Hydration: Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances (e.g. high calcium, sodium issues) are frequent delirium triggers. Hypercalcemia (“stones, bones, groans, and confusion”) and hyponatremia are key examples to look for.

- Medications: Review drugs! Many medications can cause confusion – e.g. opioids, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, steroids. Polypharmacy and drug interactions are often factors. Also consider drug withdrawal (e.g. alcohol, benzodiazepine or nicotine withdrawal) in new confusion.

- Electrolytes / Endocrine: Metabolic disturbances like hypoglycemia, renal or liver failure (think hepatic encephalopathy), thyroid dysfunction (severe hypo- or hyperthyroid states) can present as confusion. Always check glucose promptly and review metabolic panel (see “confusion screen” below).

- Environment: A sudden change in environment (new ward, ICU), sensory overload or deprivation (e.g. missing glasses or hearing aids), disruption of sleep, or unfamiliar surroundings can worsen confusion. Try to correct sensory impairments (ensure patients have their hearing aids, glasses) and provide orientation cues.

It is very common to see multiple factors at play (e.g. an elderly patient with baseline dementia + UTI + dehydration + new opioid analgesia all together). Keep a broad mind and address every potential contributor you find.

Treating the Cause

In parallel with investigations, do a thorough bedside review for common contributing factors that might not show up in blood tests.

Some key steps:

- Medication Review: Meds are a major cause of delirium. Check the drug chart for any recent additions or dosage changes – e.g. opioids, benzodiazepines, sedatives, antihistamines, anticholinergic drugs, or steroids can tip someone into confusion. Also ensure the patient isn’t in withdrawal from something they normally take (benzodiazepine, alcohol – alcohol withdrawal delirium is important to recognize). If you find a likely culprit, discuss holding or reducing it (safely) – e.g. opioid-induced confusion might improve by lowering the dose.

- Treat Pain and Discomfort:

- Uncontrolled pain can be an unseen trigger. Assess pain even in confused patients – look for non-verbal cues (grimacing, guarding, vital sign changes). If the patient has an injury (e.g. hip fracture), surgical site, or another painful condition, ensure adequate analgesia is given.

- Work together with nurses and physiotherapists and members of MDT to resolve this.

- Similarly, look for other physical discomforts – are they retaining urine (a distended bladder can cause agitation)?

- Do they have a full rectum (constipation)? These basic issues are easily treated and can significantly clear someone’s consciousness once relieved.

- Check for Infection Sources: Even before labs return, do a full top-to-toe exam looking for infection.

- Chest – listen for crackles or wheeze (pneumonia, COPD exacerbation).

- Urine – any smelly or cloudy urine, dysuria (if patient can report)?

- Abdomen – consider constipation, or signs of peritonitis. Skin – any cellulitis or infected wounds/IV lines?

- Sinuses or dental infections in some cases.

- Meningitis signs (if fever and neck stiffness) – though rarer in older adults, keep an open mind. Starting broad-spectrum antibiotics early in a possible sepsis delirium can be life-saving, so don’t wait for labs if sepsis is strongly suspected.

- Hydration and Electrolytes: Assess fluid status – are they dry (tachy, hypotensive, poor urine output)? Encourage oral fluids or start IV fluids if dehydrated. Address significant electrolyte derangements (e.g. rehydrate for high sodium, replace low sodium slowly if severe hyponatremia, correct hypercalcemia, etc.). Optimizing hydration can clear issues remarkably in an otherwise volume-depleted patient and should be checked before sending acute confusion screen.

- Environmental and Sensory Factors:

- Make the environment as orientation-friendly as possible. Involve nursing to ensure the patient has their glasses on, hearing aids in, and dentures in place if needed – being unable to see or hear will worsen confusion.

- Provide a visible clock and calendar, and use clear lighting (a well-lit room in daytime, dim lights at night for sleep).

- Try to have a quiet, calm environment especially at night – minimize excessive noise or staff changes when possible. Reorient the patient regularly by reminding them where they are and what time/day it is.

- Familiar items (family photos, a known blanket) can help comfort and reorient them in the unfamiliar hospital setting.

By systematically addressing these factors (meds, pain, infection, hydration, environment), you are both investigating and managing delirium causes simultaneously – the patient may start improving as you correct these issues.

Documentation and Communication

In addition to investigating with confusion screen bloods and tests, proper documentation and clear communication are essential in cases of delirium – for patient safety and for continuity of care:

- Document the confusion clearly: Note the patient’s mental state in your assessment – e.g. “Acute confusion noted: 4AT score 6/12, suggests delirium”. Describe behaviors (e.g. agitated, hallucinating, or drowsy and withdrawn) and when it started (if known). According to NICE, the diagnosis of delirium should be clearly documented in the patient’s notes (and later in any discharge summary) so that it’s recognized by all caring for the patient. This alerts the next team members to be vigilant and continue the delirium care plan.

- Record investigations and impressions: Document that you have performed a confusion screen (list the blood tests sent, that urine/culture was taken, CXR done, etc.) and any notable positive findings. For example: “Confusion likely multifactorial – urinalysis positive for nitrites (possible UTI) – antibiotics started. Also patient on high-dose codeine – holding this for now.” Write your plan to address each suspected factor.

- Involve and inform the family: Relatives or caregivers are invaluable in delirium care. Contact the family early to get a collateral history – ask what the patient’s baseline cognition and behavior are, and when was the last time they seemed themselves (this helps identify acute change). Document this collateral information. Keep the family updated that the patient is confused due to an illness (many families find sudden confusion very distressing). Explain that delirium is common and usually temporary with treatment – this reassurance helps them understand the process. Also encourage family to participate: they can help reorient the patient by talking to them, or bringing in familiar items (or simply being present) which can have a calming effect.

- Handover and care plans: Make sure to hand over delirious patients to the next shift and flag it in nursing handover. Delirium can fluctuate, so night staff should know if a patient is at risk of overnight confusion or agitation. If restraints or special measures are in place, or if the patient is a falls risk due to confusion, that must be communicated. Clearly chart any escalation plans (e.g. if patient becomes very agitated, can use haloperidol 0.5 mg PO – see below – or if deteriorates, call senior). Good documentation and communication ensure everyone is on the same page in managing the delirium.

When to Escalate (Getting Senior or Specialist Help)

A junior doctor must always know when they should escalate things to their seniors and when is the right time to bleep. Delirium can sometimes escalate to an emergency and it is crucial to know when to call for help:

- Uncertain diagnosis or red flags:

- If you’re not sure that the confusion is “just delirium” – for example, if there are focal neurological signs, seizures, or a possibility of stroke or meningitis – escalate immediately to a senior doctor.

- New confusion with any red flag (like asymmetric weakness, new facial droop, fever with neck stiffness, etc.) may warrant urgent specialist intervention (e.g. stroke team or ICU) and cover full confusion screen. When in doubt, err on the side of calling a senior review – time is brain in stroke/encephalitis cases.

- Severe agitation or risk of harm:

- If a delirious patient is extremely agitated, aggressive, or a danger to themselves or others (e.g. pulling out lines, climbing out of bed, or striking staff), get help.

- Start with non-pharmacological de-escalation (calm verbal reassurance, reorientation, involving family or a familiar staff if possible). If this fails and the patient remains a high risk, involve a senior doctor to consider short-term medication to sedate/calm the patient.

- The first-line is usually lorazepam or low-dose haloperidol (e.g. 0.5–1 mg), given orally or IM if needed. This should be used cautiously (avoid in patients with Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia, and watch QTc on ECG) and for the shortest duration necessary. Always follow local protocols for rapid tranquilization if needed, and ensure the patient is monitored.

- Involve security or restraint teams per hospital policy if the situation is out of control – your safety matters too.

- Needs closer monitoring or higher level care:

- A delirious patient who cannot be safely managed on the ward (for example, they keep pulling out IVs or are too drowsy and at risk of airway issues) may need one-to-one nursing care or even transfer to a higher care setting.

- Escalate to the duty senior nurse or consultant if you think the patient needs a special (constant observer) for safety.

- In some cases, if the delirium is due to critical illness or causes severe physiological instability (e.g. delirium from sepsis with shock), transfer to ICU/HDU is warranted. Always escalate early if you feel a patient is too unstable or unsafe on the general ward.

- Persistent or unresolving delirium:

- Most delirium improves once causes are treated, but if the patient’s confusion is not improving over days or you’re struggling to identify a cause, get specialist input.

- This could mean consulting a Geriatrics team (often experts in delirium management), or Psychiatry liaison if you need help with management of agitation or if an underlying psychiatric issue is suspected.

- Also, consider neurology consult if an atypical cause (like non-convulsive status epilepticus or prion disease) is in the differential.

- Don’t manage prolonged, refractory delirium alone – a fresh set of eyes can help uncover missed causes or suggest advanced interventions.

Conclusion

While there can be a number of things you will be rushing to complete confusion screen for delirium, do not forget one very important component of patient care, especially in the elderly: Compassion.

Be patient when dealing with confused patients, it takes time to heal. Medicine is not magic, but can definitely do wonders.

Learn to escalate timely, seek help, work closely with nurses for a holistic approach rather than pure medicine. Be a good doctor, not just a doctor. That’s what I have learnt throughout my posting in geriatrics and that will be one thing you will carry forever.